|

Wilbur's reaction to everything: concern. Photo by Kate Ota 2024 One type of writing resource book I love is a reference I can go back to time and time again. The Emotion Thesaurus by Angela Ackerman and Becca Puglisi is one such book (series!) that I keep next to me whenever I edit. However, I'm always on the lookout for more! I found 1,000 Character Reactions from Head to Toe by Valerie Howard while browsing Amazon and received it as a gift over Christmas.

Overview At just 88 pages, this book is a quick read. What you get is basically a thesaurus of body parts in order from head to toe (plus some overall things like skin). Each entry contains actions or sensations associated with that part of the body. Sometimes the action is linked to an emotion, such as cheeks burning with embarrassment. After each short list (which is never longer than a page plus a few lines) there are empty lines for you to write your own entries for that body part. My Experience I felt like each entry's list was too short. I also wanted more of them connected to a cause, like embarrassment, since a reaction is happening because something is causing it to happen. Some body parts were also conspicuously absent, so don't expect this to help you write a romantic encounter, for example. I think the empty lines are a good idea, because plenty of reactions aren't present, but it also made it look like the author didn't do enough of the research for you. Is It Worth It? This book is $5 for a paperback on Amazon and $0.99 on Kindle, though the empty lines for you to write on become useless on the Kindle. If you're trying to add more reactions and emotions to your writing, I think The Emotion Thesaurus is a better option, but if your budget can't accommodate a $17.99 Emotion Thesaurus at the moment, this book could be a good substitute or even just an entry into the concepts if the larger book is too intimidating. If your budget can handle either book, go with the more robust Emotion Thesaurus. Have you used 1,000 Character Reactions from Head to Toe? Did it help you improve your writing? Let's discuss in the comments!

0 Comments

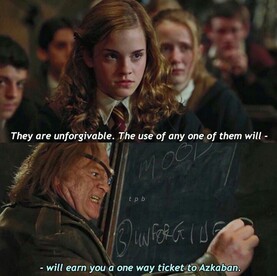

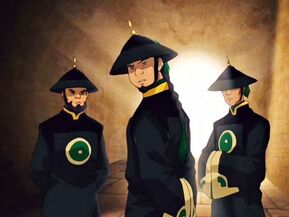

Wisteria gets its name from the American anatomist Casper Wistar. Photo by Kate Ota 2019 When I was a kid, any time I asked my dad about what a word meant, he’d start with the word's origin, the etymology. Never a dictionary-fresh definition. He had me look at the word as a thing that was built and created over time, not a stagnant object. It used to drive me nuts. “Just tell me what incongruent means, Dad!” And yet, by the time I took the ACT and SAT, I knew all sorts of random word parts and guessed my way through words I’d never seen before, to excellent scores I might add. To this day, if I hear a new word, I wonder about the etymology. It’s the most common thing I google. When I was teaching anatomy, I constantly emphasized word parts for my students. If I had continued teaching (they didn’t even offer me health insurance, so you see why I quit) then I would have made my students an anatomy word-part cheat sheet to keep for the semester. Things like osteo referring to bones, myo referring to muscles, and chond referring to cartilage would have made the list. This has obviously helped me as a reader. But can etymology help writers? Unfortunately, it can’t help with mixing up very similar words in your writing (like lay vs lie) because their etymology is also very similar. (Trust me, I checked. That was the original idea for this post but it went nowhere.) However, etymology is a huge help in worldbuilding. Let’s look at some examples. Spells in Harry Potter Most of the spells in Harry Potter have a Latin origin (a few are Greek). This does two things: one, it helps make all the spells have a unified feel; and two, it helps the readers guess or keep track of the spells’ meanings. Since HP is middle grade, it also helps the young readers learn some classic word-parts. Examples: Crucio: the unforgivable curse causing intense pain. This is from cruciate, Latin for a cross shape. And guess what the cross was used for? That’s right, it was used to torture and kill people, most notably Jesus (there’s a lot of Jesus allusions in HP.) Lumos: the light creating spell. This comes from lumen, Latin for light, and the Latin suffix os, to have. Every Day Words from Shadow and Bone Shadow and Bone (book one of the Grishaverse) by Leigh Bardugo was recently adapted into a Netflix series. (I quite enjoyed it! Though there was a lot of racism thrown at the MC, which wasn't necessary.) The main nation, Ravka, clearly has a Russian feel. One of the best ways this is accomplished is through the words. Examples: Grisha: the people who have magical powers. This comes from the Russian name for Gregory, which means watchful and connects to the biblical Grigori. Since they’re a type of army/defenders, being watchful makes sense. Otkazat’sya: the people who aren’t Grisha. It’s actually the Russian verb for to abandon, that Bardugo co-opted into a noun (which is a process called nominalization) and added the Russian suffix -sya. Bardugo added this suffix to other words in the book as well, even if the rest of the word was less Russian. A neat trick to keep the vibe of a place without totally copying the language or confusing readers for whom Russian is not familiar. Names in Avatar the Last Airbender Anyone who has seen the show will tell you Avatar is set in an Asian-inspired world. Specific cities and countries are more closely tied to specific Asian nations, and this is done through architecture, art, music, and names. Not a lot of words were made up or derived from and added onto, like the last two examples. Of course, Avatar had the advantage of being a visual medium first, so the art helped sell the overall vibe more than language needed to (like it would in books.) Examples: Dai Li: the secret police in the city Ba Sing Se. This comes from Chinese. Dai means to wear, and Li refers to a hat, specifically the pointed top and wide brim shape these characters wear. But the name has more meaning than that. Lieutenant General Dai Li was a real person in the Chinese government in the first half of the 1900s. He led a secret military police and a paramilitary fascist group. He was extremely feared and his 50,000 agents were more than spies, they could also be assassins. Zuko: the initial antagonist and eventual example of redemption. The Chinese meaning of this name can be failure or loved one, which is perfect for the character himself, as those were the two paths he saw for himself. However, it’s notable that other languages also lay claim to this name. The Filipino origin can be translated as angry or surrender—which both still work for the character. I found another origin from Zulu, where it means glory. Again, it still matches the character, if you focus on season 3. Clearly, looking at the etymology of the words in your fictional world, from spells to everyday terms to names, can give the world a sense of unity through linguistics, or add a sense of differentiation between multiple locales within your world, should you use more than one language base. Digging into the etymology of these examples was super fun for me and I learned more about the worlds as well. Building meaning into your fictional terms is a great Easter Egg for fans to enjoy beyond the story on the page. Have you ever played with etymology in your worldbuilding? Did you stick to the familiar (Latin, Greek, Germanic) or go somewhere farther from English? Let’s discuss in the comments! Sources in case you want to dig deeper: Harry Potter spell etymology Leigh Bardugo talks the etymology in Shadow and Bone Avatar the Last Airbender etymology The pictures are all not mine! Wilbur's never been outside, so this book was full of new information for him! Photo by Kate Ota 2021 Part of the same series of helpful thesauruses as The Emotion Thesaurus and The Occupation Thesaurus, The Rural Setting Thesaurus is by Angela Ackerman and Becca Puglisi. I loved The Emotion Thesaurus so much, and felt the same about The Occupation Thesaurus so I knew this would also be worth the price.

Much like the other entries, The Rural Setting Thesaurus started with some information about why the contents of this book will matter to your book. Although it did go off into seemingly less related topics like similes, metaphors, and hyperboles, it circled back to setting. This book is incredibly helpful to those still suffering from white room syndrome and if you're writing about a place you've never been. I think this book is great because not everyone has the means to travel to the wide variety of included locales (ex. desert, mountains, and beach) and now have the opportunity to describe it as if they've been there. Each entry covers the expected/typical/possible sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and textures and sensations found in the setting. It also lists possible sources of conflict the setting can cause in a scene, people commonly found there, related settings included in the book, notes and tips specific to that setting, and a setting description example. Before you think that you don't have any rural settings in your novel, this thesaurus includes what I'd consider suburban settings as well, such as rooms in a house and a classic American school's various rooms. There are also rural sights and natural locations, as you'd expect. The Urban Thesaurus listings are included in the back, and while the content doesn't crossover too much, I think some of those locations can crossover into rural or suburban settings as well (such as bakery and parking lot). So if you're looking for one specific location, be sure to check which book may have it first. (Or get both, I bet the urban one is worth it, too!) Like my Occupation Thesaurus post, I'll be creating my own entry. This seems to be encouraged, as there are more settings on One Stop for Writers (which I reviewed before.) And now, I present my unofficial contribution to The Rural Setting Thesaurus Location: Corn Maze Sights Tall stalks of corn, mice, birds, bugs, other groups of people, map or overhead photo, ladders or lookouts, weather, hay bales, signs or arrows, broken stalks where people have passed through, muddy or gravel covered paths, people getting angry, scared children, actors (if it’s themed), scarecrows or other spooky or themed props, employees or farm hands, parking lot, ticket booth, snack stand Sounds Screaming (fear or happiness), laughter, arguing, wind shaking the corn stalks, bugs buzzing, mood music (if it’s themed), chainsaws (if it’s themed or a horror novel) Smells Various snacks available (most likely fall foods like apple cider, apple donuts, pumpkin spice, roasted corn, popcorn), wet earth, ripe corn (very subtle), smells from nearby farm fields (apple orchards especially are often nearby) Tastes Various snacks available (most likely fall foods like apple cider, apple donuts, pumpkin spice, roasted corn, popcorn), NOT the ripe corn on the stalks (this is often against the rules) Textures and Sensations Wind whipping corn stalks against them, clinging to friends out of fear, fear, muddy ground sucking at shoes, rocks in the path, cold air, surprise from running into other people or actors, confusion, disorientation, defeat, excitement, corn silk running through their fingers Possible Sources of Conflict Arguing over the best path to take Getting totally disoriented and lost Arguing over whether to quit Arguing over whether to climb the ladder/look out to find a way out easier Getting surprised/scared by a rival group or actor Racing with another group Losing the group one started with and ending up alone People Commonly Found Here Teens and young adults, families, Halloween lovers, fall lovers, people from other communities, farm hands, maze employees, parents outside the maze waiting for their kids, actors in the maze Related Settings that May Tie In Farm, orchard, barn, county fair Setting Notes and Tips Corn mazes are usually only available in October, maybe in late September/early November depending on the area and weather. They can be themed, not just a scary Halloween maze, but can be themed around various charities, school mascots, or local lore. Some places with corn mazes offer more than one, of various difficulty levels. They’re most common east of the Rockies and west of the Appalachians in the US, but there are plenty close to the coasts, too. They usually have rules, such as don’t eat the corn, don’t cut through the corn, and don’t touch the actors. However, each one will vary. Almost all will have employees walk the maze before closing to ensure no one is stuck inside (however, this was not done when my friends and I got lost and we were almost locked inside.) Setting Description Example Jessica clung to Ashley as the girls’ steps squelched on the thick muddy path. Corn rose around them, higher than they could reach on their tip toes. Long strands of silk waved over their heads, as if alerting the chainsaw wielding actor to their location. The buzzing of the saw sent a chill down Jessica’s spine, but they’d been inside so long, she no longer trusted her sense of direction. They came to the end of a tunnel and had to choose. Left or right. Or perhaps backwards. The glint of a chainsaw turning a corner to the left made the decision for her. There are lots of great settings in the thesaurus, but I'm sure many more that could be added. Got any ideas? Let's discuss below! This the home page for One Stop for Writers. The image on the right changes. Overview:

One Stop for Writers is a website to help writers create characters and worlds and plot their novels. It’s powered by thesauruses, like the Emotion Thesaurus that I already decided is worth the price. Overall, the website offers fifteen thesauruses—all of the published ones and several others. At One Stop, you can create many different things to help you plan your novel. The Character Builder develops a personality, emotional wound, inner and outer motivations, fear, quirks, life, and physical traits. Character’s Fear is a similar page focused only on one character’s fear and what personality traits stem from that. Character Arc Progression asks for information from the Character Builder, but also has you consider a resolution. Emotional Progression has you lists events that occur and the emotions of the character, and how you plan to show (not tell) the emotions. Setting-at-a-Glance has you describe your setting with the five senses, as well as lighting/time of day. Emotional Value of a Setting adds symbolism and forces you to consider deeper aspects of scene that will theoretically reinforce the emotions of the characters. Scene Map (informal and formal) asks you for information about what is happening in the scene. The formal version asks more questions. The Story Map is a very general plot outline with major elements listed, generates an interactive imaged with acts 1-3 or stages 1-6 indicated. The timeline is great because you can write events as they come to mind, and then drag them around in whatever order you need. Last is the Worldbuilding Survey, which can be used to create planets down to a single household and everything in between. All of those have the thesauruses built in to offer suggestions that go together. For example, you select an emotional wound, and the website suggests fears that may stem from it. There are also worksheets and templates you can download to work offline, however these lack the connection to the thesauruses. The site also offers 47 checklists and tip sheets. Checklists can help you do things like add conflict or create a good flashback. Some of the lists include positive traits or when to show not tell. Many are also tutorials for how to use the various thesauruses, although that’s not very difficult. The website has excellent how-tos, including videos and screenshots. Most of it is very user friendly. There are cost tiers to consider. There’s a 2-week free trial, which you should absolutely use if you’re thinking of paying to play. Of note, with the free trial you cannot download pdfs of what you make and can only make one item in each category. It’s easy enough to get around those issues though, since you can copy/paste from the website into word and can delete info and remake subsequent items. I’m not being sketchy by telling you this, the website creators tell you that in the how-to-use section. Otherwise the pricing is: $9 for one month, $50 for 6 months, and $90 for one year. My Experience: I used my two-week free trial to work on the concept I had for a potential NaNoWriMo project. I’ve never done heavy outlining like this site offered, and thought the structure could be useful. Of the 15 electronic thesauruses, my favorite is symbolism thesaurus, because that’s my weakest skill. A few of them, like the texture thesaurus, were not very full, and I probably could have listed all of those entries myself. I enjoyed the character builder. It worked from the emotional wound outward, so that the character’s personality came together in an organic way. The suggests from the thesauruses were great and helped to easily build a round main character. However, if you have the print thesauruses, I think they’d cover the same information, though would be slower to navigate. Some of what you can make feels redundant, for example the Character’s Fear page is already something you fill out in the Character Builder. Perhaps it’s a short version meant for side characters. I decided to test if using this website helped me write a stronger first draft of a scene. I wrote the opening scene of my NaNoWriMo project after creating two characters, completing one Worldbuilding Survey, one Emotional Value of a Scene sheet, and a Story Map. Then I took this scene to my critique group. My critique group didn’t notice a drastic change in first draft quality from my previous WIP to this scene. They also didn’t pick up on any of the additions I made using the Emotional Value of a Setting sheet. I’ll admit that may be because I was not heavy handed with those suggestions. I did six hours of prep work on One Stop for Writers, but then I wrote 1000 words in a little over 30 minutes. Is It Worth It? If you are new to plotting, want to try plotting, or want to beef up your plotting, it’s a great resource. If you already have a plotting method that you love or if you are a panster for life, this won’t be terribly beneficial for you. I love that the site offers a free trial before getting pricey, because then you know what you’re paying for. If you’re willing to copy/paste and delete/redo then you can probably do all the planning you need during your free trial. It requires a lot of time to make what you need, but if you’ve got the time to use it, it’s fun. Overall, the free trial is for sure worth it. I don’t think the one-year trial is worth the price, unless you are an insanely prolific writer and constantly planning your next novel. The one-month trial may be helpful, but six months I can’t imagine being that useful. At least you can try it for free before beginning your next project. With one week left before NaNoWriMo begins, anyone needing help plotting may want to check this out now! Have you tried One Stop for Writers? Have you used a subscription? Did you think it was worth it? Let's discuss in the comments! The purpose of voice is to stand out, like this flower against the fence. Photo by Kate Ota in Siegen, Germany 2013 One of the things agents always talk about on twitter or their websites is voice. They want it! Please send it! And you may be left thinking what is voice? How do you develop that in your writing? I have an explanation and tips for how to develop it yourself.

What is Voice? Voice is, at its core, unique and specific word choice, punctuation, and sentence structure. These elements play together to create a narrative style that is unlike what’s been done before, or is at least interesting to read. For example, pick up a random textbook. The goal of that book is not to entertain, it’s to clearly convey information. Therefore, the word choice is going to be generic, the sentence structures are likely going to be similar, and anyone in the entire world could have written it. Which is the point. A kid is reading that textbook and you don’t want them distracted by the writer’s interesting turn of phrase. Now look at, for example, The Lightning Thief, the first Percy Jackson novel by Rick Riordan. It’s written from the point of view of a twelve-year-old boy. That book oozes Percy’s voice. Interesting word choices, variable sentence structures, unique similes. That writing style won’t be found just anywhere, and that’s the point. Voice can be the voice of a character, the voice through the book as a whole (if there's more than one point of view), or the voice of an author across their works. I believe developing your voice as an author starts with the voices of your characters, which together will be the voice through the book. Below, I focus on tips for how to develop the voice of a character. Develop Your Voice Tip #1: Monologue as Your Character The best way I’ve found to fall into my character’s voices is to talk aloud as if I was them. If you’re feeling shy about your at-home audience, you can do this in the shower or write it down as it flows out of you. Whatever you do, don’t over think it. This monologue is not going in your project. It’s an exercise to help you explore. Take what you know about the character’s personality and extrapolate. The words they use will match their mood and education level, the sentence length will match their energy level, the punctuation will match their breath. Imagine how they’d discuss what they love, what they hate, where they live, and the people around them. Do this exercise as long as you’d like until you get a sense for how this character speaks. Then try writing narration and dialogue from them. Does that voice sound unique? It doesn’t need to be other-worldly or wild, it just needs to sound like it’s coming from an interesting person. Model it after an interesting person’s speech pattern, if that helps you. If you think any random character in your book would sound like the voice you just played with, try again. Tip #2: Decide which rules to break Voice often manifests best when the speaker breaks a few classic writing rules. The basic rules will get you to textbook or essay level writing, but to be more than a bone-dry info-dump, you need to play a little. One of my favorite rules to break is to use fragments. Sparingly in narration and frequently in dialogue. That was a fragment, by the way. Did you notice it had a little more humanity in it than a full sentence? Sounded more natural, more conversational. Hence why I use them more in dialogue than narration. Some characters will use a little more purple-prose in their word choice than others. For example, a professional artist will probably have more flowery word choice than a lawyer, who might be more direct. Some characters may even use more adverbs, run on sentences, or make grammatical mistakes (that last one is for dialogue only and should really be used sparingly, unless you want your readers to think you are the one making the mistakes.) It’s important to know the rules before you play fast and loose with them, and be sure you’re doing so on purpose. Tip #3: Once You Have It, Write It Down After discovering how your character monologues and which rules they tend to break, write down their specific quirks. This will help you remain consistent through your project. I have character consistency sheets that can help point you in the general direction of helpful things to write down. This can be before you’ve written your project or after you’ve finished your first draft, whichever you find most useful. Compare voices you’ve developed for each of your narrators, or for the speaking voices of various characters. If they were all in a scene together and all speaking, could you differentiate their dialogue through their voices alone? Ideally, yes! Did any of these tips help you develop the voice of your narrator or other characters? Do you have a favorite method for finding the voice of a novel? Let’s discuss in the comments! Weather, like this fog, can foreshadow something ominous or hidden. Photo by Kate Ota 2019 Foreshadowing is much easier to add in the editing stages than in the first draft. The trick is deciding what to foreshadow, when to do it, and how. I’ve got some tips to help.

Two Major Categories of Foreshadowing: Plot Justification vs Artsy I’ve seen others call these direct and indirect foreshadowing, but I prefer my terms since it clarifies why they are being used. Plot justification foreshadowing is necessary for your plot to work. Maybe while finishing your first draft, you realize your character needs to be good at sword fighting for the ending to work. But you can’t have that skill randomly appear at the end or your readers will feel dissatisfied. Therefore, you need to plant that seed early with foreshadowing. It could be as obvious as having your character practice with a sword in an earlier scene, or as subtle as describing the fencing trophy in their living room. Checkov’s Gun is a classic plot justification foreshadowing rule. Prophecies also fall into this category, since they (often but not always) impact what the characters do in order to fulfill or avoid that outcome. The more plot relevance something has at the climax, the more justification it needs earlier to feel satisfying. What I call artsy foreshadowing is anything that hints at future events, but if removed, the plot still makes sense. To me, this is the harder of the two to include well. Events often foreshadowed this way are deaths, romantic entanglements, and plot twists to an extent. However, smaller events can be foreshadowed, too. I include artsy foreshadowing to deepen scenes or emphasize emotions or theme. It often gives a story the feeling of being cohesive and connected without being overt. Example of Plot Justification Foreshadowing: In How to Train Your Dragon, it is critical to the climax that Hiccup knows dragons aren’t fireproof on the inside. Therefore, in an earlier scene where he’s surrounded by tiny dragons, he watches as one suffers a burn inside it’s mouth from another dragon’s fire. Without this scene, the solution to the climax—firing into the giant dragon’s mouth—would feel convenient and maybe even impossible. Example of Artsy Foreshadowing: In the Great Gatsby, the narrator witnesses Gatsby reaching out to a green light across the bay. Later, the reader learns Daisy lives across the bay and Gatsby has been in love with her for ages. Without the green light scene, the reader still learns this. They still see he moved close to her in the hopes of meeting again. The plot still works. But the artistic moment emphasizes his desire and lets the reader know earlier that there’s something more to Gatsby than his parties. The green light is also a symbol, but I’ll cover adding symbolism another time since it’s a slightly different animal. How to Insert Plot Justification Foreshadowing Step 1: Identify what needs justification in the climax/conclusion This includes skills, weapons, complications, and potentially characters or settings. The climax needs to feel surprising, but inevitable based on the MC’s choices. Foreshadowing allows that feeling of inevitability. Step 2: Find two places to mention anything major, and one place to establish anything minor For example, in Hunger Games, Collins showed us Katniss’s archery skill level in her hometown while hunting and while doing a demo for the Games judges. Then it became necessary in the Games. This gives you a three-beat pattern, which you can spread between the three acts, if you use that structure. Anything minor, especially justifying a later surprise, should have one mention so as not to attract too much attention. Step 3: Write it in place How to Insert Artsy Foreshadowing Step 1: Identify what you’d like to foreshadow Can be events, character traits, or themes. Step 2: Identify how you will foreshadow artistically The content of dreams, passing remarks, jokes, how objects and people are described, names, weather, and more can be used. This tends to be subtle. For example, foreshadowing death through someone’s dinner being burned. The death of a meal! Or by mentioning birds circling overhead like vultures. Symbols can often foreshadow, as mentioned before, so these choices can get very indirect. If you want your reader to know it’s foreshadowing, make it more obvious. If you want your reader to realize it was foreshadowing later, go for a more subtle choice. For example, the classic scene in Star Wars V where Luke dreams he kills Vader, but under the mask is Luke. It foreshadows their connection, but if that scene wasn’t present, you’d still learn Vader was his father later. However, this scene is fairly direct for artsy foreshadowing. A more subtle example is Darth Vader’s name, since Vader in Dutch means father. (Not subtle if you speak Dutch or even German, where father is Vater, but it’s a long time between name reveal and parentage reveal, some viewers may have assumed it was a coincidence.) Step 3: Find where to add artsy foreshadowing Limit this to slower, character building scenes. Otherwise, it gets lost in action. (Except when it must be repeated, like a name.) Look for opportunities in Act 1 or early Act 2 to foreshadow the climax or ending, and look for opportunities in the first half of a scene or chapter to foreshadow something at the end of that scene or chapter. More than one thing can foreshadow the same outcome, so feel free to be creative and not repeat yourself. For major events, I always recommend the three-beat: two foreshadows and then the outcome. Example: 1. Vader’s name, 2. Luke’s face in the mask, 3. Vader is Luke’s Dad. For smaller events, especially if foreshadowing within a scene or chapter, one mention will be enough. Too many artsy foreshadows could result in the reader being confused as to why all these details are important or they figure out a major plot twist early. Step 4: Write it in place Did these tips help you add foreshadowing to your project? Got any tips of your own? Let’s discuss in the comments! From my point of view, this is one of the most beautiful places on earth. Victoria Falls, Zambia. Photo by Kate Ota 2011. In this entry in my Easier Editing series, I’m focusing on how to edit for point of view (POV). There are several different ways to look at POV, from the big question of who is telling the story to the details of maintaining consistent POV in a scene. All aspects need to be checked to make sure your work is in top shape.

General Point of View You’ll want to make sure you have chosen either first person, third person, or in rare cases second person POV for your project overall. First person uses I/me/we for the main character to refer to themselves, as they tell the story. Third person uses he/she/they as the author tells the characters’ story, and second uses you, as the author address the reader directly. Some writers have third person perspectives from multiple characters (separated by chapter), like Game of Thrones by George RR Martin, and sometimes they switch between third and first when switching characters (at chapter breaks), like The Alice Network by Kate Quinn. When editing, watch for scenes that don’t match your POV plan. Never allow a character written in first person in one scene, but third person in a later one (or vice versa.) Flavors of Point of View While first and second person tend to come in one flavor, third has two major styles. Third can be omniscient, in which the inner thoughts of any character can be accessed by the narrator. This is an older style, and not popular at the moment. Limited third is when one character at a time is followed closely, with no access to other character’s internal experiences. This is almost every third person book in the last decade, at least. When editing a third person project, ensure you’ve decided on which flavor you’re using, and stick to it. The sections below will help with fixing problems you find if your third limited feels too omniscient. Depth of Point of View This is difficult to keep consistent, and may be a slower stage in editing. Point of view can be shallow or deep. Deep meaning entrenched in the character’s mind, and shallow being more removed. Deep points of view include a lot of the five senses, visceral feelings, emotions, reactions, thoughts, and opinions. Every word chosen in a scene will reflect the character’s word choice preferences. Deep point of view will hopefully allow the reader to forget an author exists, and the reader will be living in the world of the story through the character. First person is deep by nature, since it’s clear from the start the reader is within the character’s mind. Third limited tends to be deep, and omniscient is shallow. If you write deep POV, part of your editing should be to ensure you’ve remained deep consistently. Ensure every scene has the POV character’s internal experiences as well as the external. Have a checklist nearby of internal experiences to check off in each scene. Whose Story is it Anyway? When selecting the character/s who will tell the story in first person or who will be followed closely in third person, make sure you are selecting the character who experiences the most drama in the scene/chapter/book. Rotating between characters forces the writer to make this decision with every scene or chapter change, which can be difficult to decide or challenging to juggle the characters. Using only one character’s perspective means making that choice once, but also prevents other characters from offering a more exciting perspective in a scene. When editing a multi-view-point project, ensure you’ve selected the most interesting character to follow in each scene. Don’t be afraid to experiment and pick a different character to write the scene from. For a single-view-point project, ensure you’ve selected the correct protagonist, and be vigilant when looking for instances of head hopping. Head Hopping Difficult to catch, point of view errors can occur at a line level, typically in limited third or first person perspectives. This happens when the internal experiences of a non-point-of-view-character are suddenly on the page. It’s also known as head hopping. This error can be overt, like inserting another character’s thoughts, or accidental, like writing the scene as if watching a movie, instead of from within a character’s head. Consider the following example: I bit my apple then offered it to Tommy. “No thanks.” He wasn’t hungry yet. Often justified as being information your POV character could infer, this type if information is something the POV character can’t know for sure. Therefore, it’s technically hopping into the other character’s (Tommy’s) head. Take a look at the fix: I bit my apple then offered it to Tommy. “No thanks.” Maybe he wasn’t hungry yet, since he’d eaten three oranges half an hour ago. We still aren’t sure why Tommy says no, and he’s not saying why. But by going beyond a statement, and into a clear opinion, the POV character justifies their guess, giving the reader more information about the characters/scene. POV mistakes can also be harder to spot. Consider the following example: The teacher called my name, and my face reddened. Seems innocent enough. But, when sitting in a classroom like this character, can you see your own face redden? No. Other characters can see it though, thus this is a subtle POV error. Take a look at the fix: The teacher called my name, and my face burned. The burning sensation is internal to the POV character; thus, this sentence remained in their POV. The reader will instantly know the character means they’re blushing. Instead of telling, you’ve shown us—from the character’s perspective. Double win! What aspects of point of view do you watch for during your edits? Did this list help you on your editing journey? Let’s discuss in the comments! My cat, Clue, displaying his usual emotion: hungry. Photo by Kate Ota 2020 Overview

The Emotion Thesaurus: A Writer’s Guide to Character Expression by Angela Ackerman and Becca Puglisi is a resource book which lists entries for one hundred thirty emotions (in the second edition.) You choose an emotion, go to the entry, and read the definition and lists of physical signs and behaviors, internal sensations, mental responses, acute or long-term responses, signs the emotion is being suppressed, which emotions it can escalate or deescalate to, and associated power verbs. There is an introduction section explaining how to use it and some character development items to keep in mind. It’s part of a larger series of thesauruses by these authors, which includes the emotional wound thesaurus, the positive trait thesaurus, and more. My Experience I heard about this book from several sources, and debated buying it, since an emotion thesaurus sounded like a thesaurus with fewer words. I bought a physical copy from my local indie for $17.99 (plus tax and shipping because of COVID.) I was pleasantly surprised that it’s more of an encyclopedia than a traditional thesaurus. I’ve been using it mainly for its intended purpose: to better show, rather than tell, characters' emotions. Especially for characters who do not have a point of view. The list of physical signs and behaviors is my favorite and I’ve used something from it every time I’ve opened the book. I also used it to deepen my point of view characters by thinking about which emotions they have chronically through the plot. That’s when I love the long-term response section. I’ll definitely keep using this as I edit and for the next books I write. Is it Worth It? Yes! I was skeptical at first, but I highly recommend this for anyone who struggles to have their characters emote. If you’re in the planning stages, it’s also great for character development. It’s $17.98 on Bookshop (the multi-indie-bookstore website, check it out.) There’s a digital version too, though perhaps it's harder to navigate since it's not a traditional cover-to-cover read. I’m probably going to check out the other books in their series because I’ve loved this so much. Have you used The Emotion Thesaurus, or the other books in Ackerman and Puglisi’s series? Did you find it worth it? Have you found other similar books? Let’s discuss in the comments! Sometimes it's better when things are cut, like these flowers my husband gave me for Valentine's 2018. Photo by Kate Ota 2018 Cutting filler words isn’t about lowering your word count. In fact, if you only cut filler words, you might remove 2% of the count. If you’re here to lower your 200k manuscript to a more easily published range, this is not the post for you. This list of words should be considered a guideline for words to cut to strengthen the voice, specificity, tone, and overall word choice of your manuscript.

Just remember, not EVERY instance of these words should be cut. Find each and consider if the sentence is stronger without it. 1. Very An easy place to start, replace every “very x” with a stronger, more precise adjective. This will add voice and varied word choice. See Robin Williams’s famous Dead Poet’s Society speech. 2. Down Not every down must go. It can be necessary, but often is not. Consider the following sentences: He sat down. He sat. They tell you the exact same thing. Therefore, the streamlined option is best. 3. Up Same idea as down. 4. That In formal writing, that may be required. However, in creative writing, that is often implied in a sentence and the words flow without it. Consider the following sentences: She hadn’t considered that he might want ice cream. She hadn’t considered he might want ice cream. A subtle change, but the word that does nothing to enhance the meaning or style of the earlier sentence. 5. The I know what you’re thinking. There is no possible way to avoid the. But not every the is created equal. Consider the following sentences: The driver of the other car hit the brakes. The other car’s driver braked. We have two ways to delete the in this example. First, by combining the ideas of the driver and the other car by making the other car possessive of the driver. Second, by changing hit the breaks to the more precise verb braked. Your eyes may skim over the because it’s so common. Read your work aloud to hear clusters of the. 6. Many A vague word, though it has its place. If you replace many with a more specific amount/value, you show the reader how many, instead of telling them indirectly. Consider the following sentences: She visited Disney World many times. She visited Disney World every year since she was five. The second implies she visited many times, but it also tells you more about the character. It implies her socioeconomic status and shows how committed she is to her trip. Maybe the character is very type A and plans her entire year around the trip. By being more specific than “many,” you’ve now added layers to the sentence. 7. Some/Sometimes/Somehow Vague, although once again it has its uses. More specificity will help enhance meaning. Consider the following sentences: He wished he could pay her back somehow. He didn’t know how to pay her back, but wished he could. The first sentence’s use of somehow leaves too much room for the readers to wonder. Is the guy stuck on the mechanics of paying her back? Is it because her gift was so valuable, he can’t repay her? Is he at a loss of ideas? The second sentence clarifies just enough information to keep going—it’s because he had no ideas. The some/sometimes/somehow words leave too much room for interpretation that can trap readers in their own wonderings instead of reading on—even if the answer is only a few sentences away. 8. Racial Slurs I don’t care why you want to use them. I don’t care if they are “historically accurate.” Your audience is not people born in 1850, it is people who are alive right now or will be in the future, and we better have moved on from that kind of language. If you must reference a slur, this is a tell-don’t-show moment. Consider the following sentence: He continued his racist rant with a smattering of despicable words, but Jane tuned him out. 9. Start/Begin This is useful if a character begins an action, but can’t complete it due to an interruption. However, it’s often used to show a continuing action instead. Avoid mentioning the start and dive into the action. Consider the following sentences: He shoved his sister and began to run. He shoved his sister and ran. The second sentence shows something taking place immediately before he ran, but by telling us he ran, you also imply he began running. Consider the following sentence: He shoved his sister and began to run, but she grabbed his ankle and he fell. Here, the inclusion of began is fine, because it tells what he was trying to do, and maybe he managed a step or two, but his action was interrupted. Without the began to, the reader may assume he ran far away, then wonder how his sister reached his ankle. Here, the use is justified. 10. Had Another common and required word. However, in certain instances, especially in past tense, had isn’t required to make the sentence work. Consider the following sentences: She had forgotten to turn off the stove again. She forgot to turn off the stove again. You could argue the first makes it sound like a past event in comparison to a moment in a past tense story. However, if the rest of the scene makes it clear she’s not in the kitchen, perhaps arriving home to a burned down house, the reader will read know she forgot to turn off the stove in the past. Trust your reader, they’re smarter than you think. 11. Just This one is my weakness. I throw in just all over the place. However, it is rarely necessary. Consider the following sentences: Just as he sat for his break, the fire alarm rang. As he sat for his break, the fire alarm rang. Both have the same clear sense of order: sitting followed by alarm. The just adds little if any information. 12. Suddenly Most things are sudden, if you think about it. What’s often described as sudden are unexpected things or events. Consider the following sentences: Her phone rang suddenly, and she sat up in bed. Her phone rang, and she sat up in bed. The character’s action of sitting up shows the unexpectedness of the phone ringing. And since phones, and most other noises, don’t ease you into the sound, the reader will know it’s a sudden event. Once again, trust your reader. 13. Was/Is Another required word often overused, especially in description. However, reworking sentences can reveal more information in a similar amount of words, or even transition from telling to showing. This can also be paired with overusing had in description. Consider the following sentences: She had blonde hair. It was knotted and shoulder-length. She had green eyes and was six feet tall. Her blonde hair reached her shoulders. Full of knots, it gave her the unkempt appearance of a freshly-woken child, despite her six-foot frame. By avoiding is/was and even some uses of had, the description required a little reworking. It ended up with more information about how the narrator views the character being described. The second set of sentences is far more personal than the police-bulletin-like description in the first example. 14. Seem Most appropriate for use when a character is guessing how another feels, seem is often used in description as well. And it is far less useful there. Remove how something seems and replace it with what something is. Consider the following example: The house seemed haunted. The house’s broken windows, creaking floors, and endless spiderwebs sent chills up her spine. Rather than tell you how the house seemed, the second example shows you how the house made a character feel—and her reaction lets readers know she thinks that house could be haunted. Get out of there, Honey. 15. Whole Entire Whole means entire. Entire means whole. Pick one and stick to it for voice consistency. A character may say this in dialogue, of course, but you want to streamline the narration so the author is invisible. 16. Every Single Similar to whole entire, this phrase can easily be found in dialogue. But in narration, the word single is not helpful in clarifying the word every. Consider the following sentences: He baked every single cookie with love. He baked every cookie with love. The second sentence tells the reader the same information as the first, in fewer words. Single does nothing for you. 17. Back Like many other words, back can be necessary for a sentence to work. However, it’s used in the wrong places frequently enough that it made the list. Consider the following sentences: She turned back to him, hoping to catch his eye. She turned to him, hoping to catch his eye. Even if he is behind her, the reader will understand that turning to look at someone sometimes requires turning all the way around. The word back doesn’t benefit the sentence. 18. Does Often tossed in narration to add emphasis to a verb, the emphasis is lost when read later and sounds stilted and old fashioned. It can work in dialogue if given italics for emphasis, but should be used lightly. Consider the following sentences: Adding coffee to the recipe does make a difference. Adding coffee to the recipe makes a difference. You can see how in dialogue, adding does with italics for emphasis could show a character making an argument for adding coffee. However, in narration, it comes off as a little defensive (especially since it was written before anyone could argue with the writer’s point) or overly formal. 19. Verb + To Another required word, to will be all over your drafts. However, some instances of to (paired with another verb) can be replaced with one stronger verb. Consider the following sentences: Have you been to Venice? You have to go in spring. Have you visited Venice? You must go in spring. Both been to and have to can be replaced by stronger, single-word verbs. These types of replacements can be hard to spot in your draft, but consider each instance of to and if it can be strengthened. 20. As You Know Not only is this unnecessary to include—because if the character hearing the words knows already, then why is the other character saying this phrase—but this is a red flag for what is called maid and butler dialogue. This is a term from stage performances where maids and butlers discuss what they already know in order to let the audience know what’s going on with the boss/upstairs characters. This was great when there was no narration, but you have narration on your side in novels. If two characters both already know things, they won’t acknowledge they already know, and they won’t discuss what they already know. One way around this is to have a newbie character draw information out of those who know, thereby educating the character and the reader. 21. Probably Do you know how many times I wrote the word probably in this blog post and deleted it in editing? It was in every entry on this list. And I cut it every time. Why? It wasn’t needed. Consider the following sentences from the previous entry: They probably won’t discuss what they already know. They won’t discuss what they already know. Granted, it is possible characters could discuss a topic they both already know, so including the word probably is mathematically correct. However, the second sentence is stronger, shorter, and easier advice to follow. I wrote that sentence for an audience seeking help for a problem—overusing the phrase as you know. If I left the word probably in place, my readers might agonize over if their characters are the exception. By removing the word probably, I am signaling your characters aren’t the exception and adding more pressure to follow the advice. Know your readers, know what your goal is, and you can decide if you need accuracy (a statistical report or scientific paper) or readability (entertainment). 22. Slightly/a Little/Adverbs in General While these words add uniqueness to a description, they also add confusion. How slight is slightly? How little is a little? (This is the problem with most adverbs, and the reason editors/writers say to cut them!) Replace these adverbs with more description or more precise adjectives. Consider the following sentences: He smiled a little as the king drink from his slightly poisoned cup. He smirked as the king drank from his poisoned cup. The second sentence showed the man’s action more clearly, including some emotion associated with the word smirk. The slightly didn’t need to be present, after all a slightly poisoned cup is still poisoned. But what if he’s poisoned enough to be sick, but not enough to die? Excellent question. That still counts as being poisoned. 23. Looked/Watched/Noticed/Other filter words Number twenty-three on our list is really more of twenty-three through forty. Filter words are used to filter the setting through the character then to the reader. Most writing today attempts to place the reader as deep into the character’s mind as possible. Therefore, words reminding the reader that the reader is not the character will be jarring and push the reader out of the story. Consider the following sentences: She watched her sister walk to the house. Then she heard a knock on the door. Her sister approached the house. A knock shook the door. If the reader is in the character’s head, then they don’t need the reminder that the character saw something. Anything visual on the page is assumed to be seen by the point of view character. Any noise is heard by them, any smell/taste/feeling is sensed by the character in the moment the reader reads the words. The character should have opinions and reactions to what they sense, but you don’t need to tell a reader explicitly that the character sensed it. Once again, trust the reader! What words do you consider filler? Do you have crutch words you use too liberally in your first draft and find yourself deleting a hundred times? Let’s discuss in the comments! My cat, Wilbur, semi-recreating the cover of Save The Cat! Writes a Novel. Photo by Kate Ota 2020 Overview

Save the Cat! Writes a Novel by Jessica Brody is a plot-focused writing craft book based on the popular screenwriting technique by the same name. The book has two major parts: the description of the Save the Cat! Plot structure, which has fifteen sections; and a description of ten major genres with required genre elements and examples of books in those genres with their own Save the Cat beat sheets. These genres are more specific than things like thriller, fantasy, etc. and in fact, cross those bookstore-shelf-genre lines. I got my paperback copy from a local indie bookstore for $17.99. My Experience I read the book over several days. I took the time to highlight main points and flag pages I knew I’d need later. Rather than write a new story from scratch, I used the book to analyze my current WIP. The beat sheet revealed I was missing a few key scenes, which is why my WIP felt rushed and too easy at the end. I also discovered that I’d subconsciously been doing some of the beat sheet elements, like the B-Story character. Every chapter felt helpful and relevant. Is It Worth It? The beat sheet for Save the Cat! Writes a Novel can be found online, I’ve even read it before. With explanations. But the book was so well written and organized that it made a huge difference in my understanding of the method. Having a physical copy to mark up and come back to during my edits (which I’ve done several times) has also been helpful. I don’t think I’d have gotten as much from the ebook version, and I normally only read ebooks, so that’s not me being snobby. Overall, was the book worth 17.99 (plus shipping because COVID)? YES! I highly recommend it for writers needing help with plotting, whether you’re a plotter who will use it before you start, or a pantser who will use it after your first draft is done. Have you read Save the Cat! Writes a Novel? Did you think it was worth it? Or maybe you have another writing book recommendation! Let’s discuss in the comments! |

Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed