|

A lab I worked at in 2013. Why did I photograph a sink? Who knows. Nearly every science fiction story includes a scene in a lab. Sometimes a murder mystery, medical drama, or other genres include a scene like this too. A scientist in a white coat explains to the protagonist and side characters information necessary for the plot to advance. It’s more interesting than getting an info dump in narration, so it’s a nice device. But this trope is often riddled with errors.

I’ve worked in several labs, most at universities, but also beyond a campus boundary. Here are my top tips for writing an accurate lab. 1. Where’s the safety equipment? Anyone working in the lab (either active in the scene or mentioned in the background) is going to be wearing some basic personal protective equipment (PPE.) That white coat I mentioned? It’s not for show. It’s for chemical spills. Adding one more clothing layer can buy time to run to the emergency shower in the corner. Clothes will be ruined, but at least that caustic acid won’t get to tender human skin. Other safety items: safety glasses (yes, on TOP of prescription glasses. No, it’s not comfortable), gloves (usually not latex, unless it’s a surgical suite. Nitrile is more common in labs now. They’re still stretchy, but they don’t smell), closed toed shoes (high heels do NOT count), and pants. Don’t forget the safety shower (always over a drain, usually has a bright yellow sign or handle to grab attention), and eye wash station (usually attached to the sink.) If your characters must be in the lab, these are all solid items to mention to ground the scene. 2. Meetings, especially with non-scientists, are almost never in the lab. Labs are a mess. They’re highly sensitive, full of breakable equipment, and house toxic chemicals. No one wants a crowd of laypeople wandering their lab while they’re doing an experiment. That’s a one-way ticket to ruined data. Meetings should be set in conference rooms or at most the lead scientist’s office. There will still be plenty of visuals, maybe even a demonstration. But as cool as labs are, in reality there won’t be a tour. This might help save you the trouble of describing a unique lab setting, which can be a challenge if you’ve never spent time in any labs. Besides, calling everything “equipment” or “machines” won’t benefit your reader much as those terms lack specificity. Placing the characters in a familiar type of setting (office, conference room) can help offset the unfamiliarity of the information the scientists will present. 3. The lead scientist is usually not working in the lab. Assuming this is a big enough lab, the lead scientist, also known as primary investigator (PI) at universities, is usually busy. As a professor, they might be teaching, travelling for conferences, writing grant proposals, etc. The lab will be filled with lots of other scientists, including lab technicians, post-doctorals, PhD students, undergrad interns, the lab manager, etc. And keep in mind, not everyone in the lab has a PhD, so your characters shouldn’t address everyone as Dr. So and So. 4. Labs need money to run. Not only do they need to pay the employees, but labs need to constantly buy more machines, chemical supplies, office supplies, glassware, cleaning supplies, and—if animals are involved—lots of food. Labs are always seeking money, usually through grants from foundations, but also fundraising, or a parent company if it’s outside the university setting. This is going to be a major factor on the mind of whatever character is explaining the science to your protagonist. Consider where the lab is getting money, and if that would affect any characters or plot points. 5. The ratio of success to failure is not what you think. For every successful experiment, a lab probably has dozens of failures. And I don’t mean nothing happened, I mean the data is so random the results are meaningless. Statistics play a giant role in interpreting final results, and the scientists will have set up boundaries before starting that define “hypothesis is supported” and “hypothesis is not supported.” Most of the time, the data shows the latter, but not in a defined pattern that means anything else. It’s very frustrating, and if you look up scientist memes, you’ll see a lot of joking about failure. In terms of your writing, this means when your protagonist is shown a super cool new machine, it’s not version 2.1. It’s more like version 89.8, and it likely took years to perfect. (Unless aliens are involved, but even alien scientists have failures.) 6. Scientists will never say they proved anything. This gets misinterpreted all the time. No matter how outstanding the results of an experiment, their original hypothesis is never proven. Scientists will say their hypothesis was supported, which may support a larger theory. However, if asked, a scientist will not say their hypothesis was proven. I think of this as leaving the door open. A scientist should always be willing to look at new data and interpret it independently, even when new data may contradict an old hypothesis that earlier data supported. Theories are supported by many supported hypotheses, and laws (like the law of gravity) have so far been shown as never contradicted. When your scientists speak, make sure they never say they’ve proven anything. Discovered, supported a new or alternate hypothesis, challenged previously held theories, defied laws, all of those are better phrases for science fiction than the word prove. Did this list help you with your laboratory scene? Are you a scientist and have any more tips and tricks for fellow writers? Let’s discuss in the comments!

0 Comments

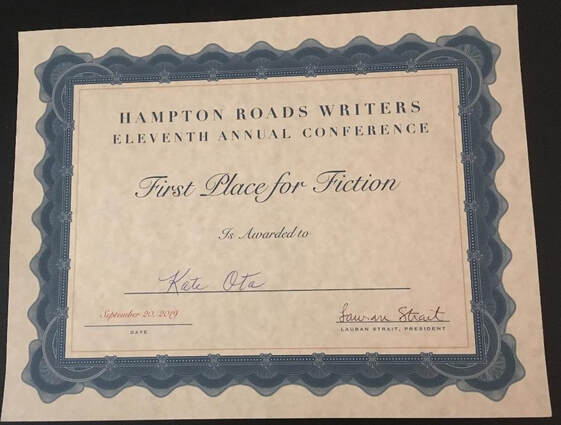

Exciting news!

This weekend (Sept 19-21st 2019) was the 11th annual Hampton Roads Writers Conference in Virginia Beach, VA. I submitted a short story to the short fiction contest. The judge was Edmund R. Schubert, which was exciting since he has over 50 published short stories! I was incredibly honored to win, especially considering the other writers who entered. Now the question is, can I get my winning short story published somewhere? I'm going to try! Keep you posted. Photo is from the Moroccan Garden in the Wilhelma Zoo in Stuttgart, Germany. Taken by Kate Ota in 2013. Sometimes you don’t have any vacation time. Sometimes it’s too expensive. Sometimes life gets in the way. Whatever the reason, you may not be able to travel to the places you feature in your writing. But you shouldn’t let that limit what you can write!

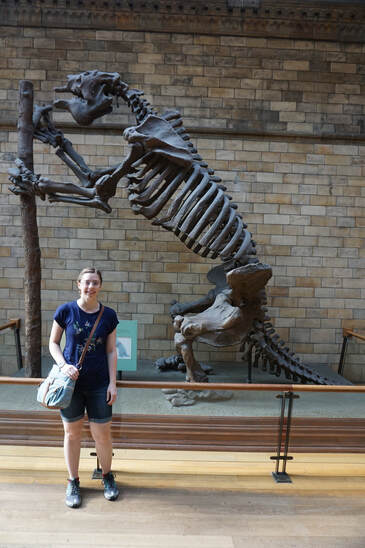

I’ve written about Ireland, Spain, and Southern France—all places I’ve never been. How did I do it? Research, of course! Here are my top tips for writing about places you’ve never been. 1. Learn the history. You don’t have to go back to ancient times, but you absolutely need to know major wars, political history, and cultural history. Let’s be real, Google is the easiest source for this. And you’re not writing non-fiction, so you’ll find enough of an overview for you to get the main points. Feel free to get creative though, YouTube has lots of history videos, including history of fashion, which can be full of gems. 2. Know the differences between your country/city and theirs. My favorite source for this is blogs by college students studying abroad. They tend to pick up on lots of day-to-day details, and usually point out the “this is so different!” factor. Travel blogs can also be helpful, though they tend to focus on tourist attractions. 3. Give yourself a google maps street view tour of the city you’re writing about. It will give you a sense of what the buildings look like, what people are wearing as they walk down the street, and what cars are popular. YouTube may also offer videos posted by tourists of their various walking or driving tours. 4. Check the weather. Weather is well documented, so even if it’s not currently the season in your book, you can get any information you want. How cold was it in December in Oslo? When does the sunset in Buenos Ares in June? Is it a dry heat or a humid heat in Kansas? Keep in mind how weather has changed over time. Are they in a drought? Are hurricanes more common than they used to be? These details can help your scenes feel grounded in your location. 5. Interview someone from your chosen location. I know this isn’t always an option, but this is your chance to use your network. Your friends may have friends who live, have lived, or even just spent a vacation in that city. You never know what great information they can offer. 6. Read books or watch movies about the location—preferably non-fiction. Take everything with a grain of salt, you never know when that author or director took creative liberties. But if it’s written by a native of that locale, these sources can be goldmines. 7. Pretend to plan a trip there. This can reveal lots of things you hadn’t thought about before. Is there public transportation (that goes anywhere useful) or would you need to rent a car? That will dictate how your characters travel. Is the city tourism focused or off the beaten trail? In foreign countries that could be the difference between everyone speaking English and no one speaking English. This is also a great way to learn about the food, based on recommendations on places like Yelp and Trip Advisor. 8. Learn the local food. Not only should you look at restaurants there, but you can look at contemporary and historical recipes posted online. You can also check Instagram for food photos posted by locals to get a sense of everyday meals. This is another thing that study abroad students will discuss often, particularly if they had trouble finding things in grocery stores. (For example, you can’t find sour cream in Germany.) 9. Know current events. For locations in the US, you can easily find local news stations on Facebook to watch clips, maybe even a local paper to read online. For international locations, especially non-English speaking, this is less straightforward. For that, you’ll need to rely on major news sources. BBC does a great job of covering International news. You’re going to want to know about current elections and political climates and social issues. Keep in mind, cities tend to be more progressive than rural areas. A news source may discuss social issues occurring in a city one way, but if you’re writing about a nearby rural region, things will be different. 10. Listen to local music. Almost every state has a song about it. Every state will also have a popular genre of music, like country, rap, pop, bluegrass, etc. You can play it in the background to get into the mentality. Other countries will have their own styles of music, both traditional and current. European countries (and Australia) have entries in Eurovision every year, they’re all on YouTube. Most Eurovision songs are in English, so that can help you get a sense of their music without a language barrier. Keep in mind, music is going to be played in public, like various stores, malls, and outdoor events. Odds are, your character will hear music, so embrace it. Have you written about a real place you’ve never been? What methods did you use? Did you find these tips helpful? Let’s chat in the comments! Photo is me standing in front of the fossil of a giant sloth at London's Natural History Museum. Photo credit to my husband. One of the toughest parts of writing is doing background research, and doing it well. Details like the names of various sword shapes, how memory function works, and the physics behind a laser-weapon may not make or break your plot. But inconsistencies and inaccuracies will cause some readers to put your book down, and never pick up any of your books again.

So let's discuss how to find accurate information! 1. Google Yes, just google it is my first tip. You'd be surprised at how easy it can be to find reputable sources. Remember that .edu and .org are often your best friends. A random blog post, or even a wikipedia page are not enough if you want to be confident about your topic. If you find conflicting information, write both pieces of information down and come back to it later. Google the newest science advances too. This can be excellent for sci-fi writers who want to dream up futuristic tech. New tech can inspire you to extrapolate that into what will be used 100 or 1000 years from now. 2. Museums I went to the Natural History Museum in London (I was in London for other reasons, I didn't fly over an ocean for a WIP). But I used the opportunity to do research for my next project, which includes many paleolithic species. I took great photos of the skeletons, read all their posted info, and used myself as a measuring stick to get the scale right. (After all, I needed to know if a giant sloth would loom over a person or be about the same size. Per the photo above, it will loom). There are tons of museums around the world which you could visit to get inspiration and research for your work too. Yes sci-fi too, you can't forget science museums! 3. Find an expert or five Use google scholar to look up academic papers about your area of interest. If the article is behind a paywall, politely email the professor who wrote it, and 99% of the time they'll be happy to send you a pdf. It costs them nothing. They don't make money from the published version anyway. Once you've read their paper, you can also ask them questions about the topic. They may have other papers, or even on-going research they could chat about. Other types of experts include people who work/worked in the field outside academia. They may have websites with blogs about their experiences or published interviews. 4. Read other books that cover the topic And then look at their resources. Maybe they list a certain museum, academic, or other resource in their acknowledgements. If it's non-fiction, they'll have a bibliography. Unlike the internet, you can almost always trust that traditionally published books were fact checked. The newer the publication the better, as it will have the most up to date information. For particularly dense/complex topics, you can google classes (aerospace engineering 101, for example) and see what textbook is required for the students. Old copies are available online for pretty cheap, especially at the end of a semester. 5. Libraries This ties into 4 well, but people often forget about their local library. You can talk to a librarian for suggestions, browse books in both non-fiction and fiction, and use their internet too. Some libraries have study rooms you can take over. This can not only offer you so many amazing resources, but it can help keep you focused on working since it's a quiet environment. Plus, who doesn't love their local library? Did this post help you on your research journey? Do you have any other tips for how to find the information you need to better build your SFF worlds? Let's discuss in the comments below! Photo is Estes Park, Colorado 2011. Taken by Kate Ota Some caveats to this post: I lived in Colorado for nineteen years and moved away for college in 2011. I’ve been back, but places change. I lived in Fort Collins, which is north of Denver (45 minutes to an hour depending on traffic) and in a region known as the Front Range. Other regions may vary.

So, you want to write a book set in Colorado. Or maybe just a few key scenes. Perhaps one character grew up there and the book is set somewhere else entirely. But you’ve never been. This post is for you!

Are you a writer who found this helpful? Maybe you were hoping for some specific information not listed here. Are you a Coloradoan who agrees? Or maybe a Coloradoan who disagrees? We can discuss in the comments! |

Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed