|

This post has been on my to-do list for a while. Back in January, I contacted a professional freelance editor about getting a developmental edit. I worked with Jeni Chappelle, who has a great website and newsletter and she has participated in RevPit, a pitch contest to get a free developmental edit. I ended up purchasing what she called a Manuscript Critique, which has the same type of feedback as her developmental edit, but includes a couple fewer things (no list of resources, fewer calls, etc.). I wanted to discover what type of feedback a paid edit would get me vs a free beta read from my writing groups and some reader friends. Is a developmental edit/manuscript critique different or better than a beta read?

I want to emphasize one of my points here: having others beta read your book is expected by agents before your query. (It's so expected that you don't need to mention it in your query.) However, no agent will reject your work solely because you didn't have a developmental edit. That type of edit might help you solve problems that then take your manuscript from a rejection to an acceptance, but: No professional editing is required in order to sign with an agent. My experience with Jeni Chappelle was awesome. She gave me incredible feedback, and our call together made me so inspired to work on my novel again. She was genuinely enthused about my project and was such a nice and caring person. If you're considering a developmental edit/manuscript critique and she seems like a fit for your story and budget, I recommend her. My beta reader pros and cons are based on several years' worth of beta feedback on my current project and three previous novels. I've worked with betas in my writing groups and friends who were more readers than writers. Your beta experience will vary. Choose wisely and know when you've gotten enough beta readers to give you feedback (you can have too many.) Overall, getting a developmental edit is significantly different from receiving beta reads. In my experience, the developmental edit was better specifically for big-picture feedback, but that's what it's designed for. I would never skip beta reading, with or without a developmental edit, because the beta feedback's granularity and variety is also incredibly useful. A gif from The Road to El Dorado where the character say "Both. Both is good." What have your editing experiences been like? Have you worked with editors you recommend? Let's discuss in the comments!

0 Comments

A visual representation of a developmental edit. Made on Canva by Kate Ota, 2023 This week I'm discussing a new experience my writing group engaged me in: a developmental edit. I'd never done one before, so I read about what they entail and what to look for before starting the process and did another refresher after I finished reading the manuscript. I thought sharing my experience could help someone else who either has been asked to do a developmental edit, wants to attempt to developmental edit their own work, or is curious about what this entails.

What is a Developmental Edit? A developmental edit is what I think of as an "early stage" edit, so you're not polishing sentences, you're polishing structure and plot and character arcs. Big picture stuff that could cause you to change huge sections of the story. No point fixing a sentence in a scene that's about to be removed. A dev edit is performed after drafting (at the earliest) but before line/copy edits. In the case of my writing group, it was done in lieu of a beta read. If you hire a professional to do a developmental edit, it is generally done after beta reading. How Do You Developmental Edit? As I read, I tried to keep in mind the big picture items: plot arc and character arc. The story was pretty linear, so structure wasn't a big concern in this case. However, if reading a non-linear story, be sure to keep an eye on structure too. I made some notes in line, but not as often as I do for beta reads. I didn't correct every small typo I came across unless it affected my reading/understanding. After reading, I put together an edit letter. There are lots of outlines online for what an edit letter should contain, so I followed one of those to make sure I hit the big points: positive feedback, setting, characters, character arc, pacing, dialogue, and plot holes. I kept my feedback a big picture as possible--don't write an entire page about one setting's single problem, or one line of dialogue that didn't fit. Elements of the Edit Letter Positive Feedback: This is huge to include in a developmental edit. Since this writer was going to get edit letters from the entire group of us, that could lead to an overwhelming amount of suggested edits. It's crucial to include what worked well, so that the author knows what NOT to change, and so they don't feel disheartened if the edit letters are long or require a lot of work. Setting: Even if set in the real world, the setting will still matter to the reader. Include if you could picture the setting in each scene, what elements were often missing (think sights/sounds/smells/tastes/touches), and if you understood when the scenes took place (night/day, years, seasons, etc.). Feel free to call out great things here too, of course, especially settings you felt worked well in contrast to ones that didn't, so the author can look at their own work to see what they did and pull that into the less successful scenes. Characters: For this section, I talked about all the characters except the main character and their arc, which is the next section. Here is where you should things like the number of named characters (overall or in a particular scene were there too many? Too few?), the names of characters (were any too similar? Did the author accidentally use a celebrity/infamous/famous character name?), and the purpose of side characters (could any be combined? Did you mix any up? Was there someone you felt was missing?). Positive feedback can go here too, like naming a favorite side character and why, mentioning a great character moment, etc. Character arc and pacing: I followed Save The Cat Writes a Novel as my guide for when certain beats should have hit, and used that to inform me on pacing, though often I could tell by gut if anything was running too long or happening too soon. Save The Cat acted like a nice quantitative measurement to back me up and help the author figure out how much to move their beats. The same is true for pacing plot and pacing the character arc. They should be two separate sections in the edit letter, despite the similar method. Character arc is the beating heart of a novel, so be sure to pay special attention to it: did the character complete their arc successfully? Did they have a lowest moment? Was the character arc driving the plot arc or vice versa? (The "correct" answer for that one will depend on genre, though agents right now love to talk about character driven stories.) Dialogue: Feedback here should include whether the dialogue felt natural in general (there will always be exceptions, like a character who is using a second language might be a little more stiff), if dialogue from different characters felt too similar, and if the dialogue to narration balance felt correct. That last one will depend on genre and taste, but go with your gut. This is also a place for positive feedback: did anyone have a great one liner that made you laugh? Did any character have stand out dialogue in general? Plot Holes: A little more general than the plot beats discussed in the pacing section, the plot hole section is where you discuss other problems with the plot or world. Even if set in the real world, there can be holes (for example: you may have to tell your author that Interstate 80 doesn't go through Colorado, it goes through Wyoming). More often, you'll need to point out questions that come up around "why did the characters do X and never even thought of the much easier method Y?" You may, but you don't have to, suggest possible solutions. However, don't get attached to your ideas, as the author may come up with a different solution that works better for them. If there are other thoughts or comments you have left over, feel free to add more sections. For different genres, you may need other sections such as Romance, Magic System, Alien Culture, Mystery Elements, etc. Every story will be different, so feel free to write an edit letter that best suits the manuscript you're editing. In the end, you'll send your edit letter to your author and hope for the best. Keep in mind, everything you're written in your letter is a suggestion, not a legal requirement. If the author loves and incorporates all of your feedback, hooray! If the author ignores every word you wrote, well, it's their novel. Odds are, something in the middle will happen, and that's great too. All you can hope for us that the author takes away at least one thing from your letter to make their book better in their eyes. Some Quick Don'ts

Have you ever done or received a developmental edit? Was it worth it? Do you recommend your editor? Let's discuss in the comments! If you're friends with any writers, there may come a time when you're asked to beta read their book. Maybe you're a writer yourself, maybe not, but either way beta reading is different from reading a typical book. If you've never beta read before and don't know how, this post is for you! Here are five steps for how to beta read.

Step 1: Upfront Questions Before you agree to beta read, ask the writer some key questions. Your goal is to determine if you're the right audience for this book. Ask for: genre, age group, word count, brief pitch.

Step 2: Set Expectations After you agree to beta read, ask the writer what their expectations are.

Step 3: The Read Now you're ready to read.

Step 4: Summary After your finish reading, you may have some overall thoughts to put together in a summary.

Step 5: Letting Go

Ready to go beta read? Have more advice for beta readers out there? Let's discuss in the comments! Views from around Snowbird Resort. The bottom right is the deck where we had most of our meetings. Photos by Kate Ota 2022 I've teased this post for a while and it's finally here! I recently attended Futurescapes at the Snowbird Resort in Utah, and in the past I virtually attended Futurescapes in 2021. Futurescapes is a multi-day workshop focused on first pages (about 25), queries, and synopses, in which you and a small group (up to seven) of other writers work with a professional (author, agent, or editor) to improve your work. In my experience, the group has cycled between mentors for each critique item (pages, query, synopsis). I commented on my virtual experience previously, but now I figured I would write about how the in-person experience differed. That way, if someone is deciding between applying to the virtual workshop or waiting for an in-person version, they can see how both experiences worked out. Let's do some pros and cons.

As you can see the in-person experience had more pros and more cons than the virtual. Honestly, the virtual felt like a slightly more in-depth version of my usual critique groups but with a professional thrown in the mix. The in-person really felt like a workshop and a special treat because of the immersion. However, I recognize that I am privileged to be able to take time off work, have the money to attend, travel, and eat at the workshop, and have the physical mobility to travel to and within the resort. I also didn't experience altitude sickness, though many others did (I was born at altitude so it's my home turf). So, I fully recognize that virtual may be the better option for others. I will not make that call for you.

Overall, I am so grateful for both of my Futurescapes experiences. I won't be sharing much of what I learned at the in-person workshop, because a lot of it was either really tailored to me and won't be useful for others or is the type of advice that the professionals get paid to give and I don't want to steal their intellectual property. Agents and authors gotta eat too. Futurescapes is for you if one or more of the following applies:

Futurescapes is NOT for you if any of the following applies:

That's my experience with Futurescapes! Will I attend again in the future? Well, I hope I'm offered rep by an agent before then, and therefore won't qualify. If you're debating attending but have questions for me, feel free to leave a comment below. This might be how your soul feels after a rough critique. Pick up those pieces and start editing. Photo by Kate Ota 2019 I’m in the editing phase of my book, which is always the longest, and I’m soliciting feedback from many sources. And then getting all that feedback. I’ve written about critique groups and how to critique, but never explained my methods for what happens next. It can be overwhelming to receive a lot of feedback at once and some people will set that aside and not use it out of a sense of dread. Here’s my method for tackling feedback.

Step 1: Take Notes During the Critique If you are doing a live critique, take notes as people talk. Even if they will send you an annotated document later, they might say something spontaneous that you don’t want to lose. You can decide if you want to write down who says what, if that matters to you. For example, if someone who shares the character’s identity says “I’d change X about how you portray Y about this character” I make sure to write down who said that so I give their opinion extra weight. If people repeat the same comment, I add a little x2 or x3 to a comment to save time. When I see this, I know this is something I need to change. If people disagree, I write who was on what side (ex. John said he likes this character but Betty hated him). This allows me to later say, aha so Betty hated this character and this other element, I wonder if fixing that element then changes her opinion on the character. Most of the time though, it may just come down to people's opinions and knowing who said what won't really matter. I also take notes if someone says something that sparks an idea in my mind. I’ll mark this with “note from me” so I don’t later think someone else was being rather forward with ideas. Step 2: Consolidate Your Notes I take all the notes I receive and transfer them into one document. I use track changes and comments in Word and will edit the document with ALL of the edits sent to me, regardless of if I agree or not. This is not the time to judge comments, only copy them. I add my notes from the live critique to the relevant scenes/chapters so I don’t have to scroll to the bottom of the document. In the end, I usually have a very marked up document, but at least it’s only one. Step 3: Prepare Your Mindset One thing people have a hard time with when receiving feedback is how it feels emotionally. It can feel like people hate your writing or you as a person or both. You need to go into your edits with the following mindset: everything everyone has written is only to help you. This needs to be your mantra. I realize there are bad actors out there who will send hate through the internet, and that's a risk you take. However, especially if you take my advice about trying live (or virtually-live) groups, you'll find that other writers really want to help. Everything everyone has written is only to help you. They are trying to help you make this book better and every edit choose to take is doing that. One more time before you dive into edits: everything everyone has written is only to help you. Step 4: Make the Edits While I receive my edits in Word, I write in Scrivener. This is because I love Scrivener for novels in general, but it has the added bonus of forcing me to think about every single edit rather than just hitting the accept button. I work linearly through the document, and will save big edits (such as over used words throughout or all of the dialogue needing tweaking, etc.) for the end. The exception is if I’m re-writing a significant portion of the scene, that is something I’ll do first, then edit anything that carried over. Here’s the sticky point for some people: how do you decide which edits to take? To me, it depends on the category of edits:

The nice thing about getting critiques is that no one watches you make the edits. Don’t feel guilty for saying no to a comment, and don’t feel like you’re a bad writer for taking one. The key to editing is humility: we're all human, we all make mistakes, and we can fix those mistakes. Step 5: Final Polish Once I’ve finished transferring in my edits, I send it through an AI grammar checker. Mine is ProWritingAid, but I’ve heard good things about lots of other programs. Which program I use is not a hill I’d die on. This is just a final polish and helps me catch some smaller, subtler errors. Usually these are errors generated by the process of editing itself. It also helps me make sure I’m not too pronoun heavy, that my sentences vary in length, etc. I recommend these programs as a final polish, but not an initial one. You need humans for that! Editing Resources: There are a ton of editing resources out there. Checklists for individual chapters, beat sheets for entire plot lines, etc. If you find yourself returning to the same problems, keep some of those resources nearby. I like to keep The Emotion Thesaurus handy because I consistently don’t show enough emotion with my characters. That’s my feedback wrangling process. Did it help you? Do you have your own method you’d like to share? Let’s discuss in the comments! Every flower in this photo represents an instance of the word just in the first draft of my last manuscript. (Photo by Kate Ota 2019) One of the biggest psychological hurdles in joining a new critique group is figuring out how to critique another person’s writing. This can be especially difficult when critiquing memoir or personal essays and you’re discussing events that actually happened to the author. Of courses fiction is just as much a writer’s soul, so it’s still difficult. Some people join and hold back on critique, but that's not why you joined the group. How do you critique? And do it in a way that endears you to the group, rather than ostracizes you? As a member of two long-running critique groups (one I’ve met in person and one only online, so far) and several one-off groups, I have plenty of advice for how to make this work.

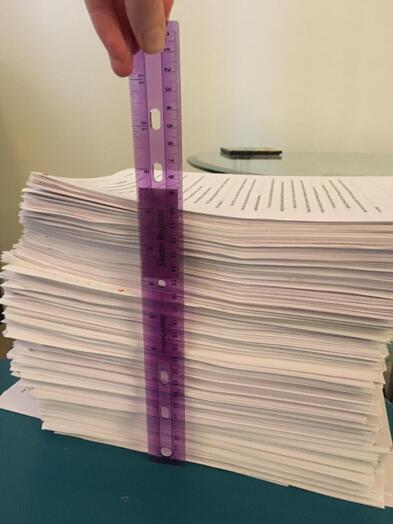

Identify Your Strengths Before you even look at their pages, consider what you think is your strength in writing. And don’t be humble here, you’re only thinking this to yourself. It can be big picture items, like noticing plot holes in your work (or published books you’ve read), or it can be very small, like knowing every comma rule. Your strengths can also come from other hobbies and jobs, like being able to shoot a bow an arrow (handy for fantasy and historical) or understanding anatomy (useful for crime, thriller, horror, or biopunk). Know what you’re good at, and have that be forefront in your mind as you go in to the work. Every person who critiques has a different strength, and will offer a different piece of the puzzle to the author. Do A First Pass Without Critiquing This isn’t always possible, especially in groups that live read then critique. But, if you can, don’t mark anything (unless it’s a huge, distracting issue) on your first pass. Then do a second pass. Things that may have confused you in the first read, you see may have had a purpose later in the story. Then you can mention in your critique that you know why the author wrote something, but that the way it was written was confusing for you. I recommend that because often a writer will see “this is confusing” and think to themselves, “the reader just needs to wait and see.” If you mention that you did wait and see and it still wasn’t as smooth as possible, the author may take your comment more seriously. If you have time, a third pass read aloud can help you catch smaller sentence structure items, accidental rhymes, repeated words, and over-long sentences. Phrasing You may be thinking that editing isn’t the hard part, it’s how to phrase your critique to the writer. No one likes being told their writing wasn’t perfect, and a writer new to critique may easily misunderstand good-intentioned feedback. Even a veteran, like me, can sometimes be having a bad day and feel more sensitive to critique. You never know how much emotional effort a writer has put into their work, how personal a fictional story might be, or what their life is like right now. Therefore, ALWAYS critique the words on the page and NEVER critique the writer. To be sure you’re following this rule, never write the word “you” in your feedback. For example, let’s say there’s blatant sexism on the page. It’s too soon to tell if it’s the character’s voice, or the writer’s actual opinion. Hey, maybe this character’s arc is about becoming less sexist (hello Sokka from season 1 episode 4 of Avatar: The Last Airbender). But maybe you aren’t seeing that on the page in the sample given. Rather than saying, “hey, you’re being sexist here,” you can phrase it like, “The character is saying pretty sexist things in this paragraph. This made me uncomfortable. There’s a risk the audience may not root for him.” That comment cites the problem on the page (“the character is being pretty sexist here”), expresses your emotion as a reader (“this made me uncomfortable”) and gives a concrete reason why this is a problem (“the audience may not root for him”). What to Critique Need ideas for what to search for? Anything that catches your eye is good to point out, even if all you can say is “this confused me” or “I think this is wrong, but I don’t know what’s right.” If you want to stretch your muscles and look for specific items to critique, here’s a list of things I try to note: Punctuation errors, especially around dialogue Spelling errors or inconsistencies (especially names) Misplaced modifiers Pronoun errors Confusing sentences Too long sentences (generally if more than seven concepts are introduced at once) Repeated words or repetitive phrasing Overuse of common words: was/were, to, had, the, know, just, back, started/began, some, etc. Characters (consistency, round vs flat, active vs passive, too many, too similar, etc.) Voice (consistency, amount of voice, matching voice to characters, etc.) Plot logistics (internal logic, plot holes, clarity of what the characters want) Pacing (too slow, too fast) Setting/world building (is it enough, too much, logical, etc.) Consistent POV (1st/3rd/2nd use consistent, head hopping, etc.) Vague terms (big/small, fast/slow, etc.) Too many adverbs (can be replaced by description) Dialogue (stiff vs natural, fitting to character, consistent use of contractions, proper punctuation, clear dialogue tags, too many non-said tags, etc.) Telling instead of showing The Most Important Part Some people get so bogged down in what’s wrong, they forget to tell the writer what’s right. If you love a line, highlight it and let them know. Write a comment of lol, haha, or a smile next to what you thought was funny. And at the end of the document, write what you enjoyed overall, like the general ideas, the characters, the banter, really cool worldbuilding, etc. And if you were excited to read on, mention that too. This information is supremely helpful because the writer might feel like they need to start from scratch if they get a ton of structural feedback. If they know what they did well, they know what to save. Plus, it helps soften the blow of the feedback that suggests work. Miscellaneous Advice If your feedback is all written, not verbal (like an online exchange), avoid sarcasm or too much joking in your feedback, as it can be hard to interpret on the page. Exceptions may be if you know the writer extremely well. It’s okay to admit you don’t know a fix. For example, you may notice a sentence is very long, but you may not be sure where to break it up. That’s okay! You can point out issues and admit you don’t have a solution. It’s okay to make big suggestions, but don’t get upset if the writer doesn’t take the idea. You never know, you may spark yet another idea for the writer and they’ll appreciate it. Avoid phrasing feedback like it’s something the writer must do. I like the phrase “consider doing x.” Always give advice to make the existing story better, never suggest trashing it or starting from scratch. If it’s not something you’d be willing to hear about your own writing, don’t say it. Remember that critique is about improving. Only make comments with improvement in mind, never be cruel or mock the writing. How did you adjust to joining a new critique group? What do you look for when you critique? Let's discuss in the comments! Photo of feedback from three years in Tidewater Writers. Photo by Kate Ota 2020 I joined my local critique group, Tidewater Writers, in March 2017. Over the last three years, I got a lot of feedback. Seriously, look at that photo. That’s eight and a half inches of feedback. Eighteen pounds! Six of those inches (and fifteen of those pounds) are dedicated to one novel. One inch of that is all the feedback I got on chapter one alone. I firmly believe that I wouldn’t have finished my novel (currently #amquerying it!) without the constructive criticism, knowledge, advice, and overall help of my critique group. After all, when there’s a meeting every week, you feel the pressure to bring something new (or at least edited since last time) and that push got me to write the end.

Joining a critique group takes a lot of courage. Tidewater Writers is open to all, and the members who attend fluctuate, with a core group showing up most often. It was extremely welcoming, and I have zero regrets! Some people are nervous about joining critique groups, so I’m writing this post about all things critique group! Types of Groups There are two major types of critique groups: in-person and online. I’ve been part of both, but personally found the in-person critiques have been the most impactful on my writing. It’s easier to explain your opinion in person, rather than in writing, especially if you have more questions about what you’re reading than comments for it. In-person allows more back and forth, clarifications, even lighthearted jokes. Online allows more anonymity and security, and offers more partners to people in isolated locations or smaller towns. It also allows more flexibility, since you don’t have to be in X location at Y time to meet. Choose the type of group that fits your needs, but I recommend trying both and testing your comfort zones. You never know who you’ll connect with! How to Find One The easiest answer is the internet. But where? I found Tidewater Writers by googling writing groups in Norfolk. But there are more direct ways to do it. Meet Ups is a good place to do general searches for groups in any given location. This is great if you have no idea what the local critique group is called. If you know the name of a group, Facebook is an easy way to search since the odds are high they have a page. Other writing-related groups on Facebook are also great places to find online partners to trade with, especially if you join one that specific to your genre. Twitter has an active writing community under many hashtags, (WritingCommunity, amwriting, amquerying, amediting, the list could go on endlessly.) You can post asking about critique groups that already exist, or you can ask if anyone wants to form a new one. Some events exist specifically to match critique partners, so keep an eye out for those too! Let’s say you don’t want to look online. How else do you find people? Connect at writing conferences, ideally local ones, or at local writing events, like classes, book launches, and events at libraries. Wherever a writer may go, search there! Quick Dos and Don’ts Never been part of a critique group? Not to worry. Some quick tips for what to do: Do: If it’s an in-person group, bring multiple copies of your work, enough for everyone present to have their own copy, ideally. I recommend printing double sided, double spaced, twelve-point Times (or other easily read font.) Don’t: Bring only one copy to read aloud and expect line edits. If no one can see your commas, how can they catch a comma error? Reading aloud without giving copies would get you feedback mostly for flow, concept, pacing, or voice. But you can also get that feedback with copies in their hands! Do: Bring/post an unpublished work that is beyond the first draft. Don’t: Bring/post something that is already published (self or traditional) or something that is only a first draft. Already published work won’t benefit from feedback, but feedback is the point of sharing in this context. If you only want to share your published work but not hear criticism, schedule a reading at your local library or indie bookstore. A first draft is also a no-no because they’re riddled with easy to catch mistakes, like typos, autocorrections, homonym mix ups, etc. Your readers will get stuck on these tiny details and not be able to focus on bigger picture feedback that you could also benefit from. Do: Follow the rules of the group. Often there are restrictions on how much you can bring/post (word count or length in terms of time.) Some in-person groups also restrict how long anyone gives verbal feedback. Don’t: Assume you’re the exception to the rules. If you’d be unwilling to stay late to finish critiques, don’t expect others to. If you’re unwilling to read an extra thousand words, don’t expect others to. And if you are willing, don’t assume others are! Do: Give feedback about the writing on the page, any and all feedback you can give. Be constructive and offer why you think something doesn’t work. You don’t always need to offer solutions. Feel free to point out things you love as well! Don’t: Only offer feedback such as, “this was great!” or, “this was terrible.” Both are equally unhelpful. Don’t critique the writer, for example, “this makes you look like an amateur.” Don’t be mean. Do: Try out a few critique groups, if you can. Don’t: Feel obligated to return to a group if you felt unwelcome, unsafe, or that the feedback was unhelpful. The Most Frequent Feedback I Receive Over time, the group’s most frequent comments have made me more aware of what my weaknesses are. That way I can address them before going. At this point, I can read a draft and guess what each person is going to say about certain parts. I’m frequently told my early drafts go too fast, and I need to add more internal reactions and narration to slow the pacing so the reader can absorb everything. My other weaknesses are repeated sentence starts (especially the, I, and pronouns) and repeated words (especially just, back, so, and be verbs). The Most Frequent Feedback I Give I tend to also point out repeated sentence starts, since I’m sensitive to them after hunting for them in my own work. Usually, I also notice grammar issues like commas and verb agreement. Had, be verbs, to, and I are words I catch as overused. I tend to pick up on the wrong word being used, or perhaps not the best word being used, where the author could make a stronger choice for a clearer message. Most often, I make this comment about verbs. I’m about to move across the country and what I’ll miss most is my lovely critique group! We’ll keep in touch online, but I’ll miss the regular meetings holding me accountable for making progress. If you’re a writer in Bremerton, WA, leave a comment! I’d love to connect! And if this post helped you find a critique group, or the courage to try one, let me know in the comments. |

Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed