|

Weather, like this fog, can foreshadow something ominous or hidden. Photo by Kate Ota 2019 Foreshadowing is much easier to add in the editing stages than in the first draft. The trick is deciding what to foreshadow, when to do it, and how. I’ve got some tips to help.

Two Major Categories of Foreshadowing: Plot Justification vs Artsy I’ve seen others call these direct and indirect foreshadowing, but I prefer my terms since it clarifies why they are being used. Plot justification foreshadowing is necessary for your plot to work. Maybe while finishing your first draft, you realize your character needs to be good at sword fighting for the ending to work. But you can’t have that skill randomly appear at the end or your readers will feel dissatisfied. Therefore, you need to plant that seed early with foreshadowing. It could be as obvious as having your character practice with a sword in an earlier scene, or as subtle as describing the fencing trophy in their living room. Checkov’s Gun is a classic plot justification foreshadowing rule. Prophecies also fall into this category, since they (often but not always) impact what the characters do in order to fulfill or avoid that outcome. The more plot relevance something has at the climax, the more justification it needs earlier to feel satisfying. What I call artsy foreshadowing is anything that hints at future events, but if removed, the plot still makes sense. To me, this is the harder of the two to include well. Events often foreshadowed this way are deaths, romantic entanglements, and plot twists to an extent. However, smaller events can be foreshadowed, too. I include artsy foreshadowing to deepen scenes or emphasize emotions or theme. It often gives a story the feeling of being cohesive and connected without being overt. Example of Plot Justification Foreshadowing: In How to Train Your Dragon, it is critical to the climax that Hiccup knows dragons aren’t fireproof on the inside. Therefore, in an earlier scene where he’s surrounded by tiny dragons, he watches as one suffers a burn inside it’s mouth from another dragon’s fire. Without this scene, the solution to the climax—firing into the giant dragon’s mouth—would feel convenient and maybe even impossible. Example of Artsy Foreshadowing: In the Great Gatsby, the narrator witnesses Gatsby reaching out to a green light across the bay. Later, the reader learns Daisy lives across the bay and Gatsby has been in love with her for ages. Without the green light scene, the reader still learns this. They still see he moved close to her in the hopes of meeting again. The plot still works. But the artistic moment emphasizes his desire and lets the reader know earlier that there’s something more to Gatsby than his parties. The green light is also a symbol, but I’ll cover adding symbolism another time since it’s a slightly different animal. How to Insert Plot Justification Foreshadowing Step 1: Identify what needs justification in the climax/conclusion This includes skills, weapons, complications, and potentially characters or settings. The climax needs to feel surprising, but inevitable based on the MC’s choices. Foreshadowing allows that feeling of inevitability. Step 2: Find two places to mention anything major, and one place to establish anything minor For example, in Hunger Games, Collins showed us Katniss’s archery skill level in her hometown while hunting and while doing a demo for the Games judges. Then it became necessary in the Games. This gives you a three-beat pattern, which you can spread between the three acts, if you use that structure. Anything minor, especially justifying a later surprise, should have one mention so as not to attract too much attention. Step 3: Write it in place How to Insert Artsy Foreshadowing Step 1: Identify what you’d like to foreshadow Can be events, character traits, or themes. Step 2: Identify how you will foreshadow artistically The content of dreams, passing remarks, jokes, how objects and people are described, names, weather, and more can be used. This tends to be subtle. For example, foreshadowing death through someone’s dinner being burned. The death of a meal! Or by mentioning birds circling overhead like vultures. Symbols can often foreshadow, as mentioned before, so these choices can get very indirect. If you want your reader to know it’s foreshadowing, make it more obvious. If you want your reader to realize it was foreshadowing later, go for a more subtle choice. For example, the classic scene in Star Wars V where Luke dreams he kills Vader, but under the mask is Luke. It foreshadows their connection, but if that scene wasn’t present, you’d still learn Vader was his father later. However, this scene is fairly direct for artsy foreshadowing. A more subtle example is Darth Vader’s name, since Vader in Dutch means father. (Not subtle if you speak Dutch or even German, where father is Vater, but it’s a long time between name reveal and parentage reveal, some viewers may have assumed it was a coincidence.) Step 3: Find where to add artsy foreshadowing Limit this to slower, character building scenes. Otherwise, it gets lost in action. (Except when it must be repeated, like a name.) Look for opportunities in Act 1 or early Act 2 to foreshadow the climax or ending, and look for opportunities in the first half of a scene or chapter to foreshadow something at the end of that scene or chapter. More than one thing can foreshadow the same outcome, so feel free to be creative and not repeat yourself. For major events, I always recommend the three-beat: two foreshadows and then the outcome. Example: 1. Vader’s name, 2. Luke’s face in the mask, 3. Vader is Luke’s Dad. For smaller events, especially if foreshadowing within a scene or chapter, one mention will be enough. Too many artsy foreshadows could result in the reader being confused as to why all these details are important or they figure out a major plot twist early. Step 4: Write it in place Did these tips help you add foreshadowing to your project? Got any tips of your own? Let’s discuss in the comments!

0 Comments

From my point of view, this is one of the most beautiful places on earth. Victoria Falls, Zambia. Photo by Kate Ota 2011. In this entry in my Easier Editing series, I’m focusing on how to edit for point of view (POV). There are several different ways to look at POV, from the big question of who is telling the story to the details of maintaining consistent POV in a scene. All aspects need to be checked to make sure your work is in top shape.

General Point of View You’ll want to make sure you have chosen either first person, third person, or in rare cases second person POV for your project overall. First person uses I/me/we for the main character to refer to themselves, as they tell the story. Third person uses he/she/they as the author tells the characters’ story, and second uses you, as the author address the reader directly. Some writers have third person perspectives from multiple characters (separated by chapter), like Game of Thrones by George RR Martin, and sometimes they switch between third and first when switching characters (at chapter breaks), like The Alice Network by Kate Quinn. When editing, watch for scenes that don’t match your POV plan. Never allow a character written in first person in one scene, but third person in a later one (or vice versa.) Flavors of Point of View While first and second person tend to come in one flavor, third has two major styles. Third can be omniscient, in which the inner thoughts of any character can be accessed by the narrator. This is an older style, and not popular at the moment. Limited third is when one character at a time is followed closely, with no access to other character’s internal experiences. This is almost every third person book in the last decade, at least. When editing a third person project, ensure you’ve decided on which flavor you’re using, and stick to it. The sections below will help with fixing problems you find if your third limited feels too omniscient. Depth of Point of View This is difficult to keep consistent, and may be a slower stage in editing. Point of view can be shallow or deep. Deep meaning entrenched in the character’s mind, and shallow being more removed. Deep points of view include a lot of the five senses, visceral feelings, emotions, reactions, thoughts, and opinions. Every word chosen in a scene will reflect the character’s word choice preferences. Deep point of view will hopefully allow the reader to forget an author exists, and the reader will be living in the world of the story through the character. First person is deep by nature, since it’s clear from the start the reader is within the character’s mind. Third limited tends to be deep, and omniscient is shallow. If you write deep POV, part of your editing should be to ensure you’ve remained deep consistently. Ensure every scene has the POV character’s internal experiences as well as the external. Have a checklist nearby of internal experiences to check off in each scene. Whose Story is it Anyway? When selecting the character/s who will tell the story in first person or who will be followed closely in third person, make sure you are selecting the character who experiences the most drama in the scene/chapter/book. Rotating between characters forces the writer to make this decision with every scene or chapter change, which can be difficult to decide or challenging to juggle the characters. Using only one character’s perspective means making that choice once, but also prevents other characters from offering a more exciting perspective in a scene. When editing a multi-view-point project, ensure you’ve selected the most interesting character to follow in each scene. Don’t be afraid to experiment and pick a different character to write the scene from. For a single-view-point project, ensure you’ve selected the correct protagonist, and be vigilant when looking for instances of head hopping. Head Hopping Difficult to catch, point of view errors can occur at a line level, typically in limited third or first person perspectives. This happens when the internal experiences of a non-point-of-view-character are suddenly on the page. It’s also known as head hopping. This error can be overt, like inserting another character’s thoughts, or accidental, like writing the scene as if watching a movie, instead of from within a character’s head. Consider the following example: I bit my apple then offered it to Tommy. “No thanks.” He wasn’t hungry yet. Often justified as being information your POV character could infer, this type if information is something the POV character can’t know for sure. Therefore, it’s technically hopping into the other character’s (Tommy’s) head. Take a look at the fix: I bit my apple then offered it to Tommy. “No thanks.” Maybe he wasn’t hungry yet, since he’d eaten three oranges half an hour ago. We still aren’t sure why Tommy says no, and he’s not saying why. But by going beyond a statement, and into a clear opinion, the POV character justifies their guess, giving the reader more information about the characters/scene. POV mistakes can also be harder to spot. Consider the following example: The teacher called my name, and my face reddened. Seems innocent enough. But, when sitting in a classroom like this character, can you see your own face redden? No. Other characters can see it though, thus this is a subtle POV error. Take a look at the fix: The teacher called my name, and my face burned. The burning sensation is internal to the POV character; thus, this sentence remained in their POV. The reader will instantly know the character means they’re blushing. Instead of telling, you’ve shown us—from the character’s perspective. Double win! What aspects of point of view do you watch for during your edits? Did this list help you on your editing journey? Let’s discuss in the comments! My cat, Clue, displaying his usual emotion: hungry. Photo by Kate Ota 2020 Overview

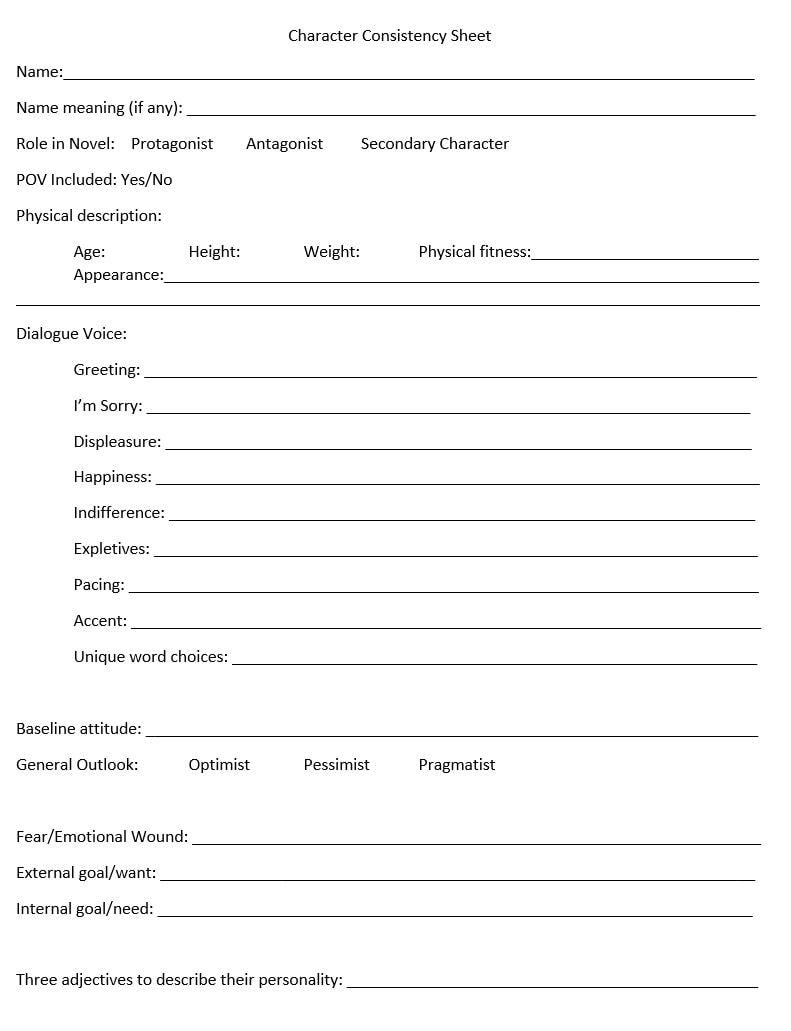

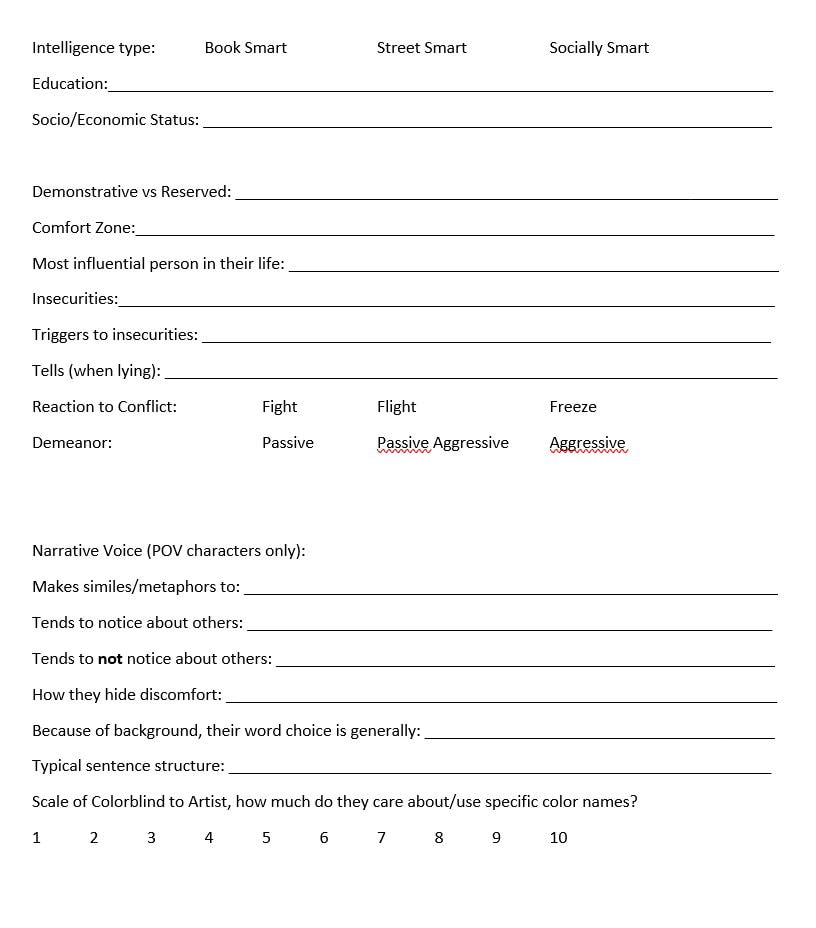

The Emotion Thesaurus: A Writer’s Guide to Character Expression by Angela Ackerman and Becca Puglisi is a resource book which lists entries for one hundred thirty emotions (in the second edition.) You choose an emotion, go to the entry, and read the definition and lists of physical signs and behaviors, internal sensations, mental responses, acute or long-term responses, signs the emotion is being suppressed, which emotions it can escalate or deescalate to, and associated power verbs. There is an introduction section explaining how to use it and some character development items to keep in mind. It’s part of a larger series of thesauruses by these authors, which includes the emotional wound thesaurus, the positive trait thesaurus, and more. My Experience I heard about this book from several sources, and debated buying it, since an emotion thesaurus sounded like a thesaurus with fewer words. I bought a physical copy from my local indie for $17.99 (plus tax and shipping because of COVID.) I was pleasantly surprised that it’s more of an encyclopedia than a traditional thesaurus. I’ve been using it mainly for its intended purpose: to better show, rather than tell, characters' emotions. Especially for characters who do not have a point of view. The list of physical signs and behaviors is my favorite and I’ve used something from it every time I’ve opened the book. I also used it to deepen my point of view characters by thinking about which emotions they have chronically through the plot. That’s when I love the long-term response section. I’ll definitely keep using this as I edit and for the next books I write. Is it Worth It? Yes! I was skeptical at first, but I highly recommend this for anyone who struggles to have their characters emote. If you’re in the planning stages, it’s also great for character development. It’s $17.98 on Bookshop (the multi-indie-bookstore website, check it out.) There’s a digital version too, though perhaps it's harder to navigate since it's not a traditional cover-to-cover read. I’m probably going to check out the other books in their series because I’ve loved this so much. Have you used The Emotion Thesaurus, or the other books in Ackerman and Puglisi’s series? Did you find it worth it? Have you found other similar books? Let’s discuss in the comments! Patterns of flower petals are beautiful and, more interestingly, consistent. Just like your characters should be. Photo by Kate Ota 2019 I recently began editing my latest WIP and have been reading editing books and consuming as much how-to-edit media as possible. I decided a fun blog series may be posting methods I've found that have made my editing process easier. First up: editing for character consistency. An online workshop hosted by the Mystery Writers of America- Pacific Northwest offered a character consistency sheet to use while editing. The example given in this (amazing!) workshop was nice, but didn’t cover most of what I need while editing. A few weeks ago, I mentioned working on character consistency using style sheets in Four Tips for Helping Your Writing Without Writing. So on a day I didn't feel like writing, and with inspiration from that workshop and some editing books, I made my own character consistency sheet. Feel free to use mine or make it your own too! Please note: this is NOT a character background sheet. I specifically left off things like their family, their hobbies, or their favorite anything. However, this can supplement or draw from a background sheet you’ve already made. The character consistency sheet is about what comes up frequently on the page—their dialogue quirks, what they look like, how emotional they are, and their narrative voice. Also keep in mind that different circumstances will make your character do or say different things. This is why the lines beside dialogue options are long. Maybe they greet friends with “Hey,” their boss with, “Hello”, and their grandmother with, “Good afternoon.” Sorry these aren't downloadable, I don't have the website capabilities for that just yet.

Did you like my character consistency sheet? What are you adding to your own? Let's discuss in the comments! |

Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed