|

There are some elements of this cover that I love, like the snake, and the room she's in, but I didn't click with how tactus is drawn or the character's face. Redsight by Meredith Mooring is a science fantasy/space opera. It came on my radar because I was hoping to find books by authors with disabilities. Meredith Mooring is blind, as is her main character, which I thought would lead to a unique reading experience. (She has a blog post about being an author who is blind here.)

As a side note, I used to work for a non-profit that dealt with donated corneas (the clear part at the front of your eye, where a contact lens sits) and getting them to patients who needed them. Through that job, I learned that there are all sorts of types of blindness and levels of sight someone can have; the term "blind" not an all or nothing situation. I'm going to refer to Korinna as being blind here for ease of communication, but some might prefer low-vision or vision-impaired. Redsight follows a red priestess, Korinna, who has always believed she is the worst trainee of her cohort. Red seers are blind, but can tap into the universe's power (tactus) to "see" (think Toph from ATLA) and navigate the stars. When Korinna graduates, she is thrust into a prestigious position as the navigator of a planet-sized ship. An advisor on board, Litia, is strange--Korinna can see her face perfectly clearly, unlike anyone or anything before. However, Litia has a secret and a plan of her own. Something I liked about Redsight was that it made it so seamless for a blind person such as Korinna to move around the ships, even when she was the only person with that need on a plant-sized ship. Because with technology that advanced, why wouldn't you make Braille (called tactile script) available everywhere? Why wouldn't you have communication tech that works for everyone? It made so much sense and I loved it. I also liked how the limited visual descriptions from Korinna made the other sense descriptions feel important, instead of how in other books they're mentioned more for ambiance than information. I also liked the relationship of red, black, and white priestesses to each other, and how one could not be dominant over the others. Something I wasn't as fond of in the book was the body horror element of the magic system. I love that there was a consequence for magic, but I couldn't really vibe with the number of times Korinna's fingernails fell off. I don't care if there was magical healing, losing fingernails is a no from me. (It got to be like that in Gideon the Ninth for me. Despite all the good stuff in there, the gore crossed a threshold I didn't know I had.) You'll enjoy this book if you enjoyed Gideon the Ninth (Sapphic, science fantasy, blood/body magic), if you want to read from a vision-impaired perspective, and if you want to see how non-visual descriptions can really stand out. This book is not for you if you're not looking for a romantic subplot, if you don't do well with literary blood/gore, or if you are looking for a space opera without magic. Have you read Redsight? What about other books from authors who navigate the world differently from the majority of people? Let's discuss in the comments!

0 Comments

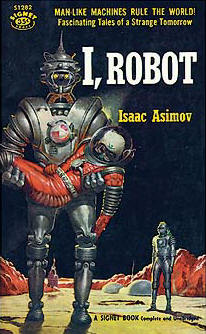

A retro cover of I, Robot depicting a scene from one of the stories within. Isaac Asimov is a famous mid-twentieth-century scifi writer of both novels and short stories. Aside from I, Robot, his most famous work is the Foundation series (which won the one-time Best All Time Series Hugo Award in 1966, kind of a big deal). He won many awards, and now some awards, magazines, and even robots are named for him. Most of his work includes robotics, and his three laws of robotics have been at the very least considered if not adapted by many who include robots in their own writing. If you're writing robots, cyborgs, or even AI in your scifi, you need to read iRobot. Plus, it's got some thriller and horror elements, and robots fit the Halloween vibe, right? So it's the perfect time to read it.

1) Just like Frankenstein, don't be afraid of a unique structure I, Robot, as it sits on a shelf today, is not how the contents were first presented. Now, it's a series of stories with an external story woven through that connected them all. Initially, these stories were published solo from 1940-1950. If all of the stories had been presented in chronological order with no external structure to guide me, I would have thought this was very choppy and didn't flow. The structure being handed to me up front made it easier to understand these were short stories stacked on each other in a trench coat. It may be a challenge to put together, but a unique structure could be just what your complex novel needs. 2) Play with your worldbuilding Each of the short stories delved into a different aspect of how the laws of robotics worked, or could inadvertently fail, and also included what was going on socially with how the world viewed robots. It was a really cool way to see how this world functioned and it was fun guessing at how the three laws of robotics would get messed up in each tale. If your story world has set laws (socially or physically), see how those laws interact, if they can fail, or if they can bend. Maybe your characters don't even understand the laws fully, so what they consider a rule is actually much more complex. Feel free to play and even write short stories about your world to get to know it more deeply. 3) Anticipate future social norms One thing I appreciated about I, Robot was that the main character, the robopsychologist being interviewed in the external structural storyline, was a woman. This was put together in 1950, and that character appears in the short stories too, so she wasn't just slapped in there for fun. While she was the only woman prominently featured as a scientist, she was so necessary. If I'd read this book and it had been all men in science despite the mid-to-late 2000s setting, I wouldn't have enjoyed it. If your writing is set in the future, think about how it will read in the future. Will that joke you made still be funny, or could it be harmful? (The gauge here is to "punch up, not down" i.e. make fun of the powerful not the people with equal or less power than you. Satire about the president: will probably age well; joke about the poor: no.) Will your inclusion of different genders (and think full spectrum here) be appreciated? Probably! So don't be afraid to think of the future socially just as much as technologically. (Though Asimov wrote a woman in STEM as a prominent character, note there were plenty of people reporting his sexual harassment of women during his lifetime. So, write as he wrote, but don't do as he did.) Those were my big writing takeaways from Isaac Asimov's I, Robot. If you're looking for the plot from 2004's I, Robot with Will Smith, you may end up disappointed. However, just think of that movie as another short story that would fit right in to the collection. It didn't surprise me that the Hollywood version was so different from the book, the same was true for Frankenstein! Have you read I, Robot or other Asimov novels and short stories? Have you learned any good writing lessons from him? Let's discuss in the comments! The Amazon cover for the book features the green classic monster, not as described in the book. Fall is spooky season and one of the main Halloween monsters is of course Frankenstein's monster, sometimes called Adam. Since it is a foundational text to scifi--the very first scifi, in fact--I decided to read the original Frankenstein by Mary Shelley. Rather than review it, I decided to write about what I learned about writing irom this classic novel (or really a novella, it was about 110 pages).

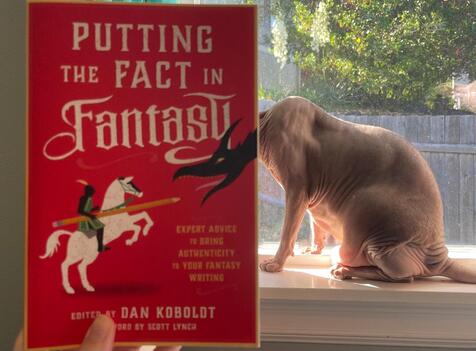

1) Don't be afraid of a unique story structure Frankenstein is actually a letter written by a sea captain to his sister about meeting Dr. Frankenstein and that man's story. So the meat of the book is "story within a story" since you know in the end things will circle back to that boat captain. At one point, the story becomes the monster's story being told to Dr. Frankenstein being told to the captain. Like Russian nesting dolls. However, this complicated structure was made very clear and even acted as foreshadowing of excitement when the start of Dr. Frankenstein's tale got a little dry. 2) Don't overdo the backstory While it may have been the style of the time, modern readers now don't need Dr. Frankenstein's life story to begin with his parents meeting. When I saw that was how the story began, I was dreading the rest. It didn't get interesting until Dr. Frankenstein left for college. So while it's good to read classics, keep in mind how very different the market is today, and don't accidentally pick up on very out of date style choices. 3) Build sympathy by showing what your characters wants most We were all a little afraid of Frankenstein's monster after his first kill, naturally, because he's not on the page much to defend himself. However, he makes it clear exactly what he wants: a lover. He is so intensely lonely and in need of contact that after he explains it, you can't avoid sympathy. There is even some sympathy for Dr. Frankenstein when he just wants to protect others. Get your readers to choose sides by showing a deep want and explaining why--and why they can't have it (yet). 4) Keep up with the latest innovations Mary Shelley was inspired by Galvanism and advances with electricity. If she'd only stayed aware of what was going on in the literary world, she wouldn't have run into the concepts that allowed her to conceive of Frankenstein. When looking for inspiration, look at innovations in fields that excite you: space, medicine, engineering, environmental science, oceanography, etc. Even keeping up with new historical finds in archaeology or anthropology, if you're more of a history/fantasy writer. You never know when you'll run into something that will inspire, so get out of your typical bubble. Those are my big takeaways from Frankenstein for writers. I will admit I was very surprised that a lot of classic Frankenstein tropes weren't in the original book--no castle, no Igor, no villagers with pitchforks and torches. He literally made his monster in his dorm room. (Try explaining that mess to your R.A.) I think he was even described as yellow, not green. So the Hollywood-ization of Frankenstein has clearly overshadowed the original for my entire experience. Kind of wild! Have you read Frankenstein? What were your writing (or reading) takeaways? What are some of your spooky season favorites? Let's discuss in the comments! Clue as a dragon. Photo by Kate Ota 2023 Putting the Fact in Fantasy is a collection of essays by subject matter experts about various topics that are often portrayed poorly in fantasy books, movies, and TV. The collection was edited by Dan Koboldt. I came across this book in an Indie bookstore and thought it would probably be helpful for my adult fantasy WIP.

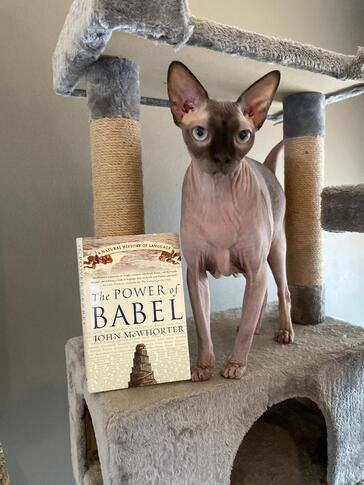

Overview The fifty essays cover topics such as history as inspiration (female professions in medieval Europe, feudal nobility), languages and culture (realistic translation, developing a culture), worldbuilding (magic academies, money, political systems), weapons (archery, soldiers, martial arts), horses (so many horses), and adventure (hiking, castles and ruins). Pretty large variety! Most entries are less than ten pages, and the entire book is only 332 in paperback. My Experience There is a large skew toward European information, but some sections specifically call out non-Western information, like the feudal nobility section which included Middle Eastern titles. Very few sections are focused solely on non-Western information. Most of the historical info is also medieval or even Renaissance, with very little historical focus on more recent time periods. Some essays in the worldbuilding section are less about time period and more about making you think more deeply about your world, which was very helpful. I marked many sections I want to return to, including one about plants. I will say, the horse section went on a bit too long. Is It Worth It? I paid $20 at an indie bookstore for a paperback copy. The ebook is slightly cheaper ($14.99) but if you want to highlight or bookmark sections that you want to think about later, a physical copy is a good investment. This book could be worth it if you're writing a historical fantasy or secondary world fantasy. If you're writing urban fantasy, magical realism, or contemporary fantasy, this book will not be as valuable to you. (Unless you're writing about horses and know nothing about horses.) This book may also be useful for other writers who are writing secondary worlds, since the worldbuilding section is pretty flexible. Bonus, there's also a section about Westerns! Overall, it was worth the price to me. Have you read Putting the Fact in Fantasy? What about the other anthology edited by Dan Koboldt, Putting the Science in Fiction? Let's discuss in the comments! Tower of Babel, cat tower, same thing, right? Photo by Kate Ota 2023 The Power of Babel: A Natural History of Language by John McWhorter was published in the very early 2000s and discusses how languages arise, evolve, split, and go extinct. Why am I writing this as an "Is It Worth It" and not a book review? Well, I realized early in the book that if I was going to create a fantasy or scifi language, this book included a lot of information about how to make a fake language feel real and not just some made up words in an English grammar scheme.

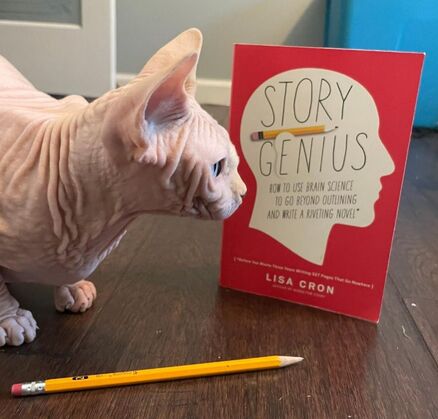

Overview This book covers a lot of ground in 303 pages, including discussing different grammatical boxes in which languages can be categorized and how languages tend to morph words (because there are reliable patterns). A lot of space is also dedicated to discussing dialects and creole languages. My Experience I enjoyed many of the interesting facts in the book, and learned so much about language in general that I'd never considered. In fact, one of the facts I read was tweeted by Merriam Webster while I was reading. What are the odds? However, it was a little dry and spent a long time explaining things. There were also a lot of Bill Clinton jokes. Is It Worth It? I got this paperback book from an indie bookstore for $17.99. If I was trying to build a language for a story, I think it would be a huge resource to get started with the basic concepts of how the language would operate. However, if you're just a linguistics nerd, or someone who got excited by the etymology in R.F. Kuang's Babel, then this is probably not the book you are hoping it is. Have you ever tried to create a language for a project? What sources did you find helpful? Let's discuss in the comments! I couldn't get the pencil to sit behind Wilbur's ear, but otherwise, it's a pretty close re-creation! Photo by Kate Ota 2023. Story Genius: How to us Brain Science to Go Beyond Outlining and Write a Riveting Novel by Lisa Cron is one of those writing books that I constantly hear about. After my lackluster experience with the similarly lauded Bird by Bird, I worried this would also be a stinker. However, I had an hour to kill at a Barnes and Noble, and when I spotted Story Genius, my curiosity outweighed my hesitance.

Overview Story Genius breaks its advice into a couple sections, but in general it gives instructions on how to plot from idea through first draft. The main focus is to create a story that has a cohesive character arc and an external plot that specifically drives that arc. It also includes how this approach appeals to the brain so well. There are templates and spots where the book instructs the reader to stop and do an exercise that builds toward having a draft. My Experience I highlighted so much of this book. From the advice on point of view to the tips and tricks for each stage of brainstorming and outlining. This book really appealed to how I usually plot anyway, but added ideas to make that even better. I can't wait to try this method, not just with a fresh story but use it on my current WIP to make sure my external and internal plots mesh well. Is It Worth It? I bought a paperback for $14.99, but if e-book is your thing it can be yours for $9.99. Honestly, this book is precisely for the type of writer that I am. I wish I'd bought it sooner, because I think I'll incorporate its method into every project from now on. I think this book is 100% worth the price! Have you read Story Genius? Have you used the method? What did you think? Let's discuss in the comments. Pipetting hand cramps are real. Photo by Louis Reed on Unsplash Have you ever read a book that depicts someone with your job, or at least in your field, and the author gets it totally and completely wrong? That happened to me recently. I work in biotech, specifically we make proteins (for example antibodies) to treat disease. I picked up a book about a scientist who was studying a protein to treat a disease and I was excited. With a pub date this year, the book led me to expect the science would be up to date.

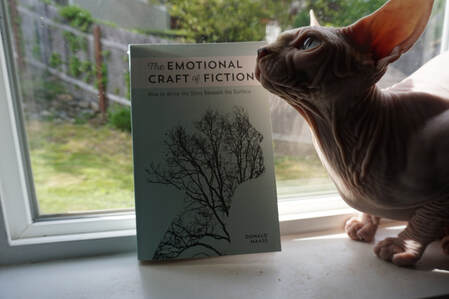

It wasn't even close. The science in this scifi was more than a decade out of date. I was so thrown off because the other tech was clearly modern (with kids having iPads, hashtags and social media, etc.). The plot was entirely based on the scientist having to do their work the very very old fashioned way. Needless to say, I struggled to enjoy the book. When I got to the end, I thought perhaps the author had never spoken to anyone about the science. However, the acknowledgement section was full of names--mostly doctors. I don't expect MDs to know HOW antibodies are produced industrially, but I do expect them to know that antibodies CAN be produced industrially. In the end, I suspect the author never spoke to anyone who actually works in biotech today. Or if she did, maybe she didn't want to change her entire plot. But wait, you say, why didn't an editor intervene? This book was self-published and likely didn't employ the kind of editor who would take it upon themselves to fact check the science. Especially given the author talked to doctors, any line or copy editor wouldn't even think about changing that sort of thing. So, what did I learn from this reading experience that I can apply to writing? If you're writing outside your familiarity zone, be it a job or another aspect of a person, be sure to speak with people who have the most direct experience with that thing. At the very least, Google recent headlines in that space. Technology, especially biotech, computer/software, and AI, have all exploded forward in the last decade. Even if you're familiar with something, reach out to an expert. Especially before pinning your entire plot on that thing! Have you ever seen your job or a similar career in a book? Did the author nail it, or totally miss the mark? Let's discuss in the comments! Wilbur mimicking the cover of The Emotional Craft of Fiction. Photo by Kate Ota 2022 I bought The Emotional Craft of Fiction by Donald Maass because it’s one of those craft books you see recommended all over the place. That and the feedback I get is pretty consistent: I nail action and dialogue, but I need to add more emotions.

Overview The book was $17.99 from Barnes and Noble. It covers the character’s emotional journey as well as the reader’s emotional journey, which is not necessarily the same. There were action points after each major topic (about 30 total) explaining where in your book to focus, what questions to ask, and therefore how to draw out that emotion. My experience I read this book in 5 days, which is about my normal pace. It’s 200 pages, and the pages are very thin (I saw the words on the other side of the paper), so it’s a thin book, but at what cost. I did a lot of highlighting, which says a lot about how useful I thought the information was, and I plan to go back when I have time and use those activity suggestions (called Emotional Mastery) to test the concepts in my current WIP. Generally, the suggestions really got my ideas flowing, so I think the inclusion of these in the book was very good. One downside, despite the many examples for his points, a few went by at lightspeed without examples. The biggest I noted was the claim that words of Anglo-Saxon origin are considered stronger than those of Latin origin. Now, I’m big into etymology, I think the evolution of language is fascinating and I’m constantly googling word origins. However, without some examples, it’s hard to see if this claim holds any water. I found two examples myself: excite (Latin) and amaze (old English, which I guess is Anglo-Saxon) and you know what? They’re pretty similar word choices, arguably synonyms in many cases. Is amaze more specific? Yes. Excite could be interpreted in a few ways. Would I say amaze is stronger? Meh. Is It Worth It? For the specific, actionable activities that are listed after each major point is made, I’d say yes. Those will probably be very helpful in drawing out more emotion from me as a writer. Is every word of advice golden? Arguably not. I say, it’s worth buying it used (if you find a copy not highlighted by someone like me) and maybe new, if you receive consistent feedback that you need more emotion in your writing (like I do). If you’re buying it just for the sake of upping something you already feel confident about, I’d say used or ebook versions to save some cash. Overall though, I see why it’s so frequently recommended among writers, and am happy I have it in my stockpile of craft books. Have you read The Emotional Craft of Fiction? What was your favorite piece of advice? Is there another book on improving emotions in your writing? Let’s discuss in the comments! Above: The main screen for WriterDuet, the online screenwriting website. I've been very happy with the free version. Below: Several versions of The Screenwriter's Bible. Readers of the blog may recall my short story The Undoing of Maggie Jinkowski, which won first place in the short story category at the Hampton Roads Writers Conference in 2019 and was recently included in the Kitsap Writers Group Anthology. I was recently asked if I'd be interested in adapting it into a screenplay format. Not a formal offer to produce it or anything, just gauging interest and seeing how it goes. I decided to give it a shot.

One of the resources recommended to me was WriterDuet, a website which already knows the right formatting for a screenplay and will help guide you in writing it. It made the basics super easy and you can use it for FREE. You can also export your project from the website to Word or a PDF. Highly recommend if you're looking to get your feet wet in screenwriting but worry about getting bogged down in formatting. Another resource I tried out was the Screenwriter's Bible. It's a big book and has resources for almost any stage of screenwriting you're in. From format to best practices to story telling. It was very helpful in explaining to me how to do some of the more complex strategies I wanted to use, like flashbacks and voice over. There are many editions of this book out there, so don't feel pressure to buy the latest, an older edition will get you started just fine. Between the site and the book, I have a pretty nice draft of my story that should work in a visual format. The hardest part was translating Maggie's thoughts to something an audience could see or hear. It helped a lot that I'd read some screenplays before, so I was familiar with what the final product needed to look like. Next step: sending the draft to my friend who showed interest and seeing what he has to say! Wish me luck! Have you ever adapted a story for the screen? Have you ever written an original screenplay? What resources helped you the most? Let's discuss in the comments! Wilbur loved The Anatomy of Story so much, he kept rubbing his face against the cover. Photo by Kate Ota 2021 I picked up a copy of The Anatomy of Story by John Truby months ago and let it languish on my shelf. I thought I’d read once I was done editing my current project or maybe when I started querying. However, as I started prepping for NaNoWriMo (during which beta readers will have my current project) I realized I should take a look to see if this book would influence my Preptober.

Overview This approximately 400-page book is $18.99 for the paperback. It’s like going from Save The Cat and The Story Equation and taking the next step in writing mastery. It includes character creation, setting, theme, and twenty-two story beats. There are numerous examples throughout as well as worksheets. My Experience The story beats are a bit save-the-cat-ish, but those were hardly the best part of the book. I appreciated the analysis of character creation and scene setting that’s explained before plot gets brought up. The way different elements are discussed on a symbolic and thematic level was mind blowing. I even found I’d used some of the techniques on accident (probably from reading so much—hence why you need to read a lot!) and with some tweaking I could make it look very purposeful and deep. I hadn’t seen many of the major examples (Tootsie, Casablanca, and The Godfather were most referred to, and I hadn’t seen The Verdict either) but they were clearly explained. I had seen some others (It’s a Wonderful Life) so it was helpful that most concepts were explained using multiple examples. It’s a dense book. I tried to read it on my morning commute and fell asleep a couple times. You really need to be awake and committed to reading it. However, it’s dense with knowledge and supremely helpful. Is It Worth It? The price was great for the amount of information and length of the book, in my opinion. If you’re a person who likes to highlight and flag craft books, then the paperback is for you. If you aren’t a highlighting type of person, then go with the e-book version to save some money. I recommend this book if you’re looking to up your plotting skills. If you aren’t a plotter, I recommend a little more clear-cut plotting book first (like Save The Cat). It’s also not about basic sentence mechanics (for that I recommend It Was The Best of Sentences, It Was The Worst of Sentences) and while it covers character, I think you need a baseline of character building first (such as understanding want vs need; I recommend The Story Equation). |

Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed