|

My mom would know what this flower is, but I don't. Photo by Kate Ota Germany 2013 Happy Mother’s Day!

One trope of MG/YA books is a dead mother (if not also a dead father). You’ll also see this trend in movies for young people—specifically Disney. So where did the trope come from and why perpetuate it? I decided to do a little digging. Where did this start? My first instinct was that this trope is drawn from fairy tales. I took a class on Grimm’s Fairytales in college and almost every birth mother was dead, often replaced by an evil stepmother. (Though, shockingly, not Snow White. Per the brothers Grimm, her bio-mom was the murderous queen.) Many academic papers have been written about the dead mother trope, both about modern and historical works. One paper summarized quite a bit for me and presented earlier theories as to why this trope exists: the high mortality rate in child birth prior to modern times (about 1% to 1.5% of mothers died during child birth in the 1600s and 1700s), socio-economic and family structure changes in the US since WWII, and Walt Disney’s bad relationship with his mother. The feminist take is that removing the mother character and forcing the father to step into her place makes the father look great and devalues the work the mother used to do to keep the household running, since Dad can do it all himself. Short version: it’s sexism. Why Kill Mother Characters? Well, parents who do a good job parenting will often prevent the sort of dangerous adventures that make MG/YA exciting. There are some stories in which parents are alive but separated from the kids, like because of a boarding school (the Weasley parents in the Harry Potter series) or war (the Pevensie parents in the Narnia series). Either way, it’s easier if the parents can’t jump in to prevent disaster. MG and YA also explore the themes of growing up and experiencing the world yourself (to a greater extent in YA, of course) which requires the removal of that parental safety net to emphasize that theme. And let’s face it, from a traditional-nuclear-family-type perspective, who is most likely to notice kid shenanigans and do something to stop it? Mom. (No offense, Dad.) TV Tropes offers the theory that dead parents are the only purely good parents in entertainment, as the others need to be stand offish or absent for plot reasons and therefore come off as terrible people. The dead are held in higher regard. It’s an interesting theory, but there are plenty of flawed dead parents in entertainment, too. And the trope page didn’t discuss mothers specifically. In The New York Times, S.S. Taylor theorized authors kill one or more parents to reassure themselves that if they died, their own real children would also find a way to be okay. A bit of therapy, in a way. Of course, that’s all been mostly about orphans, or at least when both parents are missing. But plenty of stories off Mom and keep Dad (Aladdin, Beauty and the Beast, and The Little Mermaid to name a few). You’ll notice in these movies the father-child relationship tends to be fairly strong or develops as part of the emotional arc of the story. In fact, before Cinderella’s dad dies, they’re very close in most versions. Clearly, one way to justify or emphasize a father-MC relationship is to get rid of Mom. Let’s circle back to the evil stepmother trope. This villain was typically jealous, cruel, and destructive toward stepdaughters. (We don’t see a ton of classic stories about stepmothers and their stepsons, but I’m sure they exist.) A biological mother was theoretically less likely to be this negative with their child. However, a stepmother had power/influence over the main character and would potentially be willing to treat them poorly. Since the intended audience was children, and getting deep into the psychology of why a parent may be cruel could be difficult for that audience, substituting in the stepmother may have been a shortcut to explain the bad behavior. This is a trope/cliché that’s certainly past its prime. Should You Kill Off a Mother Character? It depends. It’s a very old trope and teeters on cliché. You could use it to give your story a fairytale vibe, especially helpful if you want that feeling but aren’t doing a direct retelling. Fairytale retellings have been hot for years (I’d point to the start of the trend being Cinder by Marissa Meyer), but to stand out in this crowd, I’d recommend subverting as many tropes from the original tales as possible. That includes dead moms. Contemporary stories probably don’t need to rely on dead moms, anyway. With the recent economic crises and the feminist movements of the late 1900s, many families have both parents working. Don’t kill off the mom, just make her busy. Historical settings may have more flexibility here, since, as I mentioned before, the maternal mortality rates were terrifying for most of human history. (And they’re still not great in the US, honestly, especially for women of color!) I guess my advice is in general, no. Don’t kill off your mother characters unless there’s a very clear, specific reason she must be dead. Test your creativity and find another way to let your MG and YA characters explore their worlds. You may come up with an idea you like even more and bonus: one less dead mom character. Here are some sources for more reading on this topic:

0 Comments

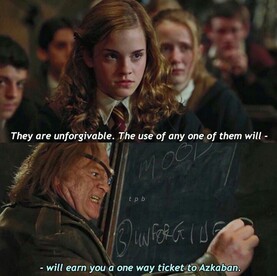

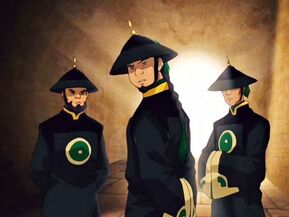

Wisteria gets its name from the American anatomist Casper Wistar. Photo by Kate Ota 2019 When I was a kid, any time I asked my dad about what a word meant, he’d start with the word's origin, the etymology. Never a dictionary-fresh definition. He had me look at the word as a thing that was built and created over time, not a stagnant object. It used to drive me nuts. “Just tell me what incongruent means, Dad!” And yet, by the time I took the ACT and SAT, I knew all sorts of random word parts and guessed my way through words I’d never seen before, to excellent scores I might add. To this day, if I hear a new word, I wonder about the etymology. It’s the most common thing I google. When I was teaching anatomy, I constantly emphasized word parts for my students. If I had continued teaching (they didn’t even offer me health insurance, so you see why I quit) then I would have made my students an anatomy word-part cheat sheet to keep for the semester. Things like osteo referring to bones, myo referring to muscles, and chond referring to cartilage would have made the list. This has obviously helped me as a reader. But can etymology help writers? Unfortunately, it can’t help with mixing up very similar words in your writing (like lay vs lie) because their etymology is also very similar. (Trust me, I checked. That was the original idea for this post but it went nowhere.) However, etymology is a huge help in worldbuilding. Let’s look at some examples. Spells in Harry Potter Most of the spells in Harry Potter have a Latin origin (a few are Greek). This does two things: one, it helps make all the spells have a unified feel; and two, it helps the readers guess or keep track of the spells’ meanings. Since HP is middle grade, it also helps the young readers learn some classic word-parts. Examples: Crucio: the unforgivable curse causing intense pain. This is from cruciate, Latin for a cross shape. And guess what the cross was used for? That’s right, it was used to torture and kill people, most notably Jesus (there’s a lot of Jesus allusions in HP.) Lumos: the light creating spell. This comes from lumen, Latin for light, and the Latin suffix os, to have. Every Day Words from Shadow and Bone Shadow and Bone (book one of the Grishaverse) by Leigh Bardugo was recently adapted into a Netflix series. (I quite enjoyed it! Though there was a lot of racism thrown at the MC, which wasn't necessary.) The main nation, Ravka, clearly has a Russian feel. One of the best ways this is accomplished is through the words. Examples: Grisha: the people who have magical powers. This comes from the Russian name for Gregory, which means watchful and connects to the biblical Grigori. Since they’re a type of army/defenders, being watchful makes sense. Otkazat’sya: the people who aren’t Grisha. It’s actually the Russian verb for to abandon, that Bardugo co-opted into a noun (which is a process called nominalization) and added the Russian suffix -sya. Bardugo added this suffix to other words in the book as well, even if the rest of the word was less Russian. A neat trick to keep the vibe of a place without totally copying the language or confusing readers for whom Russian is not familiar. Names in Avatar the Last Airbender Anyone who has seen the show will tell you Avatar is set in an Asian-inspired world. Specific cities and countries are more closely tied to specific Asian nations, and this is done through architecture, art, music, and names. Not a lot of words were made up or derived from and added onto, like the last two examples. Of course, Avatar had the advantage of being a visual medium first, so the art helped sell the overall vibe more than language needed to (like it would in books.) Examples: Dai Li: the secret police in the city Ba Sing Se. This comes from Chinese. Dai means to wear, and Li refers to a hat, specifically the pointed top and wide brim shape these characters wear. But the name has more meaning than that. Lieutenant General Dai Li was a real person in the Chinese government in the first half of the 1900s. He led a secret military police and a paramilitary fascist group. He was extremely feared and his 50,000 agents were more than spies, they could also be assassins. Zuko: the initial antagonist and eventual example of redemption. The Chinese meaning of this name can be failure or loved one, which is perfect for the character himself, as those were the two paths he saw for himself. However, it’s notable that other languages also lay claim to this name. The Filipino origin can be translated as angry or surrender—which both still work for the character. I found another origin from Zulu, where it means glory. Again, it still matches the character, if you focus on season 3. Clearly, looking at the etymology of the words in your fictional world, from spells to everyday terms to names, can give the world a sense of unity through linguistics, or add a sense of differentiation between multiple locales within your world, should you use more than one language base. Digging into the etymology of these examples was super fun for me and I learned more about the worlds as well. Building meaning into your fictional terms is a great Easter Egg for fans to enjoy beyond the story on the page. Have you ever played with etymology in your worldbuilding? Did you stick to the familiar (Latin, Greek, Germanic) or go somewhere farther from English? Let’s discuss in the comments! Sources in case you want to dig deeper: Harry Potter spell etymology Leigh Bardugo talks the etymology in Shadow and Bone Avatar the Last Airbender etymology The pictures are all not mine! |

Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed