|

Sometimes it's better when things are cut, like these flowers my husband gave me for Valentine's 2018. Photo by Kate Ota 2018 Cutting filler words isn’t about lowering your word count. In fact, if you only cut filler words, you might remove 2% of the count. If you’re here to lower your 200k manuscript to a more easily published range, this is not the post for you. This list of words should be considered a guideline for words to cut to strengthen the voice, specificity, tone, and overall word choice of your manuscript.

Just remember, not EVERY instance of these words should be cut. Find each and consider if the sentence is stronger without it. 1. Very An easy place to start, replace every “very x” with a stronger, more precise adjective. This will add voice and varied word choice. See Robin Williams’s famous Dead Poet’s Society speech. 2. Down Not every down must go. It can be necessary, but often is not. Consider the following sentences: He sat down. He sat. They tell you the exact same thing. Therefore, the streamlined option is best. 3. Up Same idea as down. 4. That In formal writing, that may be required. However, in creative writing, that is often implied in a sentence and the words flow without it. Consider the following sentences: She hadn’t considered that he might want ice cream. She hadn’t considered he might want ice cream. A subtle change, but the word that does nothing to enhance the meaning or style of the earlier sentence. 5. The I know what you’re thinking. There is no possible way to avoid the. But not every the is created equal. Consider the following sentences: The driver of the other car hit the brakes. The other car’s driver braked. We have two ways to delete the in this example. First, by combining the ideas of the driver and the other car by making the other car possessive of the driver. Second, by changing hit the breaks to the more precise verb braked. Your eyes may skim over the because it’s so common. Read your work aloud to hear clusters of the. 6. Many A vague word, though it has its place. If you replace many with a more specific amount/value, you show the reader how many, instead of telling them indirectly. Consider the following sentences: She visited Disney World many times. She visited Disney World every year since she was five. The second implies she visited many times, but it also tells you more about the character. It implies her socioeconomic status and shows how committed she is to her trip. Maybe the character is very type A and plans her entire year around the trip. By being more specific than “many,” you’ve now added layers to the sentence. 7. Some/Sometimes/Somehow Vague, although once again it has its uses. More specificity will help enhance meaning. Consider the following sentences: He wished he could pay her back somehow. He didn’t know how to pay her back, but wished he could. The first sentence’s use of somehow leaves too much room for the readers to wonder. Is the guy stuck on the mechanics of paying her back? Is it because her gift was so valuable, he can’t repay her? Is he at a loss of ideas? The second sentence clarifies just enough information to keep going—it’s because he had no ideas. The some/sometimes/somehow words leave too much room for interpretation that can trap readers in their own wonderings instead of reading on—even if the answer is only a few sentences away. 8. Racial Slurs I don’t care why you want to use them. I don’t care if they are “historically accurate.” Your audience is not people born in 1850, it is people who are alive right now or will be in the future, and we better have moved on from that kind of language. If you must reference a slur, this is a tell-don’t-show moment. Consider the following sentence: He continued his racist rant with a smattering of despicable words, but Jane tuned him out. 9. Start/Begin This is useful if a character begins an action, but can’t complete it due to an interruption. However, it’s often used to show a continuing action instead. Avoid mentioning the start and dive into the action. Consider the following sentences: He shoved his sister and began to run. He shoved his sister and ran. The second sentence shows something taking place immediately before he ran, but by telling us he ran, you also imply he began running. Consider the following sentence: He shoved his sister and began to run, but she grabbed his ankle and he fell. Here, the inclusion of began is fine, because it tells what he was trying to do, and maybe he managed a step or two, but his action was interrupted. Without the began to, the reader may assume he ran far away, then wonder how his sister reached his ankle. Here, the use is justified. 10. Had Another common and required word. However, in certain instances, especially in past tense, had isn’t required to make the sentence work. Consider the following sentences: She had forgotten to turn off the stove again. She forgot to turn off the stove again. You could argue the first makes it sound like a past event in comparison to a moment in a past tense story. However, if the rest of the scene makes it clear she’s not in the kitchen, perhaps arriving home to a burned down house, the reader will read know she forgot to turn off the stove in the past. Trust your reader, they’re smarter than you think. 11. Just This one is my weakness. I throw in just all over the place. However, it is rarely necessary. Consider the following sentences: Just as he sat for his break, the fire alarm rang. As he sat for his break, the fire alarm rang. Both have the same clear sense of order: sitting followed by alarm. The just adds little if any information. 12. Suddenly Most things are sudden, if you think about it. What’s often described as sudden are unexpected things or events. Consider the following sentences: Her phone rang suddenly, and she sat up in bed. Her phone rang, and she sat up in bed. The character’s action of sitting up shows the unexpectedness of the phone ringing. And since phones, and most other noises, don’t ease you into the sound, the reader will know it’s a sudden event. Once again, trust your reader. 13. Was/Is Another required word often overused, especially in description. However, reworking sentences can reveal more information in a similar amount of words, or even transition from telling to showing. This can also be paired with overusing had in description. Consider the following sentences: She had blonde hair. It was knotted and shoulder-length. She had green eyes and was six feet tall. Her blonde hair reached her shoulders. Full of knots, it gave her the unkempt appearance of a freshly-woken child, despite her six-foot frame. By avoiding is/was and even some uses of had, the description required a little reworking. It ended up with more information about how the narrator views the character being described. The second set of sentences is far more personal than the police-bulletin-like description in the first example. 14. Seem Most appropriate for use when a character is guessing how another feels, seem is often used in description as well. And it is far less useful there. Remove how something seems and replace it with what something is. Consider the following example: The house seemed haunted. The house’s broken windows, creaking floors, and endless spiderwebs sent chills up her spine. Rather than tell you how the house seemed, the second example shows you how the house made a character feel—and her reaction lets readers know she thinks that house could be haunted. Get out of there, Honey. 15. Whole Entire Whole means entire. Entire means whole. Pick one and stick to it for voice consistency. A character may say this in dialogue, of course, but you want to streamline the narration so the author is invisible. 16. Every Single Similar to whole entire, this phrase can easily be found in dialogue. But in narration, the word single is not helpful in clarifying the word every. Consider the following sentences: He baked every single cookie with love. He baked every cookie with love. The second sentence tells the reader the same information as the first, in fewer words. Single does nothing for you. 17. Back Like many other words, back can be necessary for a sentence to work. However, it’s used in the wrong places frequently enough that it made the list. Consider the following sentences: She turned back to him, hoping to catch his eye. She turned to him, hoping to catch his eye. Even if he is behind her, the reader will understand that turning to look at someone sometimes requires turning all the way around. The word back doesn’t benefit the sentence. 18. Does Often tossed in narration to add emphasis to a verb, the emphasis is lost when read later and sounds stilted and old fashioned. It can work in dialogue if given italics for emphasis, but should be used lightly. Consider the following sentences: Adding coffee to the recipe does make a difference. Adding coffee to the recipe makes a difference. You can see how in dialogue, adding does with italics for emphasis could show a character making an argument for adding coffee. However, in narration, it comes off as a little defensive (especially since it was written before anyone could argue with the writer’s point) or overly formal. 19. Verb + To Another required word, to will be all over your drafts. However, some instances of to (paired with another verb) can be replaced with one stronger verb. Consider the following sentences: Have you been to Venice? You have to go in spring. Have you visited Venice? You must go in spring. Both been to and have to can be replaced by stronger, single-word verbs. These types of replacements can be hard to spot in your draft, but consider each instance of to and if it can be strengthened. 20. As You Know Not only is this unnecessary to include—because if the character hearing the words knows already, then why is the other character saying this phrase—but this is a red flag for what is called maid and butler dialogue. This is a term from stage performances where maids and butlers discuss what they already know in order to let the audience know what’s going on with the boss/upstairs characters. This was great when there was no narration, but you have narration on your side in novels. If two characters both already know things, they won’t acknowledge they already know, and they won’t discuss what they already know. One way around this is to have a newbie character draw information out of those who know, thereby educating the character and the reader. 21. Probably Do you know how many times I wrote the word probably in this blog post and deleted it in editing? It was in every entry on this list. And I cut it every time. Why? It wasn’t needed. Consider the following sentences from the previous entry: They probably won’t discuss what they already know. They won’t discuss what they already know. Granted, it is possible characters could discuss a topic they both already know, so including the word probably is mathematically correct. However, the second sentence is stronger, shorter, and easier advice to follow. I wrote that sentence for an audience seeking help for a problem—overusing the phrase as you know. If I left the word probably in place, my readers might agonize over if their characters are the exception. By removing the word probably, I am signaling your characters aren’t the exception and adding more pressure to follow the advice. Know your readers, know what your goal is, and you can decide if you need accuracy (a statistical report or scientific paper) or readability (entertainment). 22. Slightly/a Little/Adverbs in General While these words add uniqueness to a description, they also add confusion. How slight is slightly? How little is a little? (This is the problem with most adverbs, and the reason editors/writers say to cut them!) Replace these adverbs with more description or more precise adjectives. Consider the following sentences: He smiled a little as the king drink from his slightly poisoned cup. He smirked as the king drank from his poisoned cup. The second sentence showed the man’s action more clearly, including some emotion associated with the word smirk. The slightly didn’t need to be present, after all a slightly poisoned cup is still poisoned. But what if he’s poisoned enough to be sick, but not enough to die? Excellent question. That still counts as being poisoned. 23. Looked/Watched/Noticed/Other filter words Number twenty-three on our list is really more of twenty-three through forty. Filter words are used to filter the setting through the character then to the reader. Most writing today attempts to place the reader as deep into the character’s mind as possible. Therefore, words reminding the reader that the reader is not the character will be jarring and push the reader out of the story. Consider the following sentences: She watched her sister walk to the house. Then she heard a knock on the door. Her sister approached the house. A knock shook the door. If the reader is in the character’s head, then they don’t need the reminder that the character saw something. Anything visual on the page is assumed to be seen by the point of view character. Any noise is heard by them, any smell/taste/feeling is sensed by the character in the moment the reader reads the words. The character should have opinions and reactions to what they sense, but you don’t need to tell a reader explicitly that the character sensed it. Once again, trust the reader! What words do you consider filler? Do you have crutch words you use too liberally in your first draft and find yourself deleting a hundred times? Let’s discuss in the comments!

0 Comments

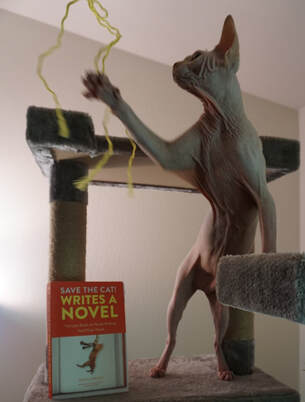

My cat, Wilbur, semi-recreating the cover of Save The Cat! Writes a Novel. Photo by Kate Ota 2020 Overview

Save the Cat! Writes a Novel by Jessica Brody is a plot-focused writing craft book based on the popular screenwriting technique by the same name. The book has two major parts: the description of the Save the Cat! Plot structure, which has fifteen sections; and a description of ten major genres with required genre elements and examples of books in those genres with their own Save the Cat beat sheets. These genres are more specific than things like thriller, fantasy, etc. and in fact, cross those bookstore-shelf-genre lines. I got my paperback copy from a local indie bookstore for $17.99. My Experience I read the book over several days. I took the time to highlight main points and flag pages I knew I’d need later. Rather than write a new story from scratch, I used the book to analyze my current WIP. The beat sheet revealed I was missing a few key scenes, which is why my WIP felt rushed and too easy at the end. I also discovered that I’d subconsciously been doing some of the beat sheet elements, like the B-Story character. Every chapter felt helpful and relevant. Is It Worth It? The beat sheet for Save the Cat! Writes a Novel can be found online, I’ve even read it before. With explanations. But the book was so well written and organized that it made a huge difference in my understanding of the method. Having a physical copy to mark up and come back to during my edits (which I’ve done several times) has also been helpful. I don’t think I’d have gotten as much from the ebook version, and I normally only read ebooks, so that’s not me being snobby. Overall, was the book worth 17.99 (plus shipping because COVID)? YES! I highly recommend it for writers needing help with plotting, whether you’re a plotter who will use it before you start, or a pantser who will use it after your first draft is done. Have you read Save the Cat! Writes a Novel? Did you think it was worth it? Or maybe you have another writing book recommendation! Let’s discuss in the comments! The Seattle skyline as seen from a ferry. Picture by Kate Ota 2015 I’m starting a new series of blog posts I’m calling: is it worth it? I’ll be telling you if various conferences, classes, and even craft books are worth the price/time. It’s all my opinion, so take my reviews with a grain of salt.

Overview The Seattle Writing Workshop was planned to be a one-day event near Seattle, WA with five sessions and fifteen classes. Lunch was not included. For $69, the conference runner would critique your one-page query. For $89, another professional would critique your first ten pages. For $29 each, you could pitch to an agent, as many as you were willing to pay for. Attendance was $189. Due to COVID-19, the conference went online, without a change in prices. However, the schedule was changed to be three days, each with five sessions each, none over-lapping. This allowed conference attendees to attend all sessions, instead of just five. Attendees also got three free sessions later. All sessions were recorded and sent to attendees afterwards. The Seattle Writing Workshop is part of a series of workshops, so if the Seattle part doesn’t apply to you, see if there is one in your area. My Experience I really enjoyed a few sessions in particular: Creating Perfectly Imperfect Characters presented by Cody Luff, How to Apply the Five Most Powerful Methods of Story Creation for Your Novel presented by Jim Rubart, What Happens After Your Get an Agent presented by agent Britt Siess, and the first pages critique panel with five agents (Cate Hart, Hope Bolinger, Jacqui Lipton, Carlisle Webber, and Leslie Sabga.) I took away enough new information from each of these to feel like I benefited from watching. A few sessions didn’t apply to me, like the ones focused on YA, MG, picture books, and non-fiction. Therefore, I didn’t watch these and can’t speak to their level of usefulness. As with any conference, as few sessions didn’t work for me. Some speakers got lost in an unhelpful tangent or spent too long pitching us their books. Speaking of pitching, I signed up to pitch some agents. Doing it over phone or zoom was a little awkward. Yes, more awkward than a face-to-face encounter. I felt like I was doing a sales call, rather than a personal pitch. However, any opportunity to have any connection with an agent is so tempting for me, that I might sign up for virtual pitches again if attending another online conference. Is it Worth It? As a virtual conference, I didn’t get my main objective: connection with fellow writers! I’m new to the area and wanted to meet a critique group, beta readers, or even just one critique partner. Alas, the virtual conference allowed for almost no contact with other attendees. There was a little-used hashtag and a Facebook group popped up afterward, but that’s not really what I wanted. If this conference happened again next year IN PERSON, I’d attend. I’d still want to meet other writers (and pitch in person if I’m still not represented.) If this workshop was virtual again, I’d pass. Unless the price was dropped by at least half. Did you “attend” the virtual Seattle Writing Workshop? Did you get any of the critiques offered and were they worth it? Let’s discuss in the comments! |

Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed