|

This post has been on my to-do list for a while. Back in January, I contacted a professional freelance editor about getting a developmental edit. I worked with Jeni Chappelle, who has a great website and newsletter and she has participated in RevPit, a pitch contest to get a free developmental edit. I ended up purchasing what she called a Manuscript Critique, which has the same type of feedback as her developmental edit, but includes a couple fewer things (no list of resources, fewer calls, etc.). I wanted to discover what type of feedback a paid edit would get me vs a free beta read from my writing groups and some reader friends. Is a developmental edit/manuscript critique different or better than a beta read?

I want to emphasize one of my points here: having others beta read your book is expected by agents before your query. (It's so expected that you don't need to mention it in your query.) However, no agent will reject your work solely because you didn't have a developmental edit. That type of edit might help you solve problems that then take your manuscript from a rejection to an acceptance, but: No professional editing is required in order to sign with an agent. My experience with Jeni Chappelle was awesome. She gave me incredible feedback, and our call together made me so inspired to work on my novel again. She was genuinely enthused about my project and was such a nice and caring person. If you're considering a developmental edit/manuscript critique and she seems like a fit for your story and budget, I recommend her. My beta reader pros and cons are based on several years' worth of beta feedback on my current project and three previous novels. I've worked with betas in my writing groups and friends who were more readers than writers. Your beta experience will vary. Choose wisely and know when you've gotten enough beta readers to give you feedback (you can have too many.) Overall, getting a developmental edit is significantly different from receiving beta reads. In my experience, the developmental edit was better specifically for big-picture feedback, but that's what it's designed for. I would never skip beta reading, with or without a developmental edit, because the beta feedback's granularity and variety is also incredibly useful. A gif from The Road to El Dorado where the character say "Both. Both is good." What have your editing experiences been like? Have you worked with editors you recommend? Let's discuss in the comments!

0 Comments

Wilbur's reaction to everything: concern. Photo by Kate Ota 2024 One type of writing resource book I love is a reference I can go back to time and time again. The Emotion Thesaurus by Angela Ackerman and Becca Puglisi is one such book (series!) that I keep next to me whenever I edit. However, I'm always on the lookout for more! I found 1,000 Character Reactions from Head to Toe by Valerie Howard while browsing Amazon and received it as a gift over Christmas.

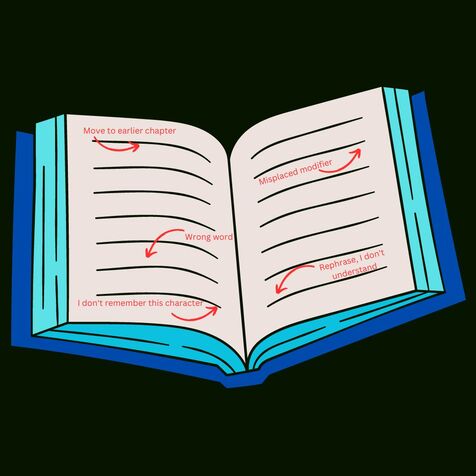

Overview At just 88 pages, this book is a quick read. What you get is basically a thesaurus of body parts in order from head to toe (plus some overall things like skin). Each entry contains actions or sensations associated with that part of the body. Sometimes the action is linked to an emotion, such as cheeks burning with embarrassment. After each short list (which is never longer than a page plus a few lines) there are empty lines for you to write your own entries for that body part. My Experience I felt like each entry's list was too short. I also wanted more of them connected to a cause, like embarrassment, since a reaction is happening because something is causing it to happen. Some body parts were also conspicuously absent, so don't expect this to help you write a romantic encounter, for example. I think the empty lines are a good idea, because plenty of reactions aren't present, but it also made it look like the author didn't do enough of the research for you. Is It Worth It? This book is $5 for a paperback on Amazon and $0.99 on Kindle, though the empty lines for you to write on become useless on the Kindle. If you're trying to add more reactions and emotions to your writing, I think The Emotion Thesaurus is a better option, but if your budget can't accommodate a $17.99 Emotion Thesaurus at the moment, this book could be a good substitute or even just an entry into the concepts if the larger book is too intimidating. If your budget can handle either book, go with the more robust Emotion Thesaurus. Have you used 1,000 Character Reactions from Head to Toe? Did it help you improve your writing? Let's discuss in the comments! A visual representation of a developmental edit. Made on Canva by Kate Ota, 2023 This week I'm discussing a new experience my writing group engaged me in: a developmental edit. I'd never done one before, so I read about what they entail and what to look for before starting the process and did another refresher after I finished reading the manuscript. I thought sharing my experience could help someone else who either has been asked to do a developmental edit, wants to attempt to developmental edit their own work, or is curious about what this entails.

What is a Developmental Edit? A developmental edit is what I think of as an "early stage" edit, so you're not polishing sentences, you're polishing structure and plot and character arcs. Big picture stuff that could cause you to change huge sections of the story. No point fixing a sentence in a scene that's about to be removed. A dev edit is performed after drafting (at the earliest) but before line/copy edits. In the case of my writing group, it was done in lieu of a beta read. If you hire a professional to do a developmental edit, it is generally done after beta reading. How Do You Developmental Edit? As I read, I tried to keep in mind the big picture items: plot arc and character arc. The story was pretty linear, so structure wasn't a big concern in this case. However, if reading a non-linear story, be sure to keep an eye on structure too. I made some notes in line, but not as often as I do for beta reads. I didn't correct every small typo I came across unless it affected my reading/understanding. After reading, I put together an edit letter. There are lots of outlines online for what an edit letter should contain, so I followed one of those to make sure I hit the big points: positive feedback, setting, characters, character arc, pacing, dialogue, and plot holes. I kept my feedback a big picture as possible--don't write an entire page about one setting's single problem, or one line of dialogue that didn't fit. Elements of the Edit Letter Positive Feedback: This is huge to include in a developmental edit. Since this writer was going to get edit letters from the entire group of us, that could lead to an overwhelming amount of suggested edits. It's crucial to include what worked well, so that the author knows what NOT to change, and so they don't feel disheartened if the edit letters are long or require a lot of work. Setting: Even if set in the real world, the setting will still matter to the reader. Include if you could picture the setting in each scene, what elements were often missing (think sights/sounds/smells/tastes/touches), and if you understood when the scenes took place (night/day, years, seasons, etc.). Feel free to call out great things here too, of course, especially settings you felt worked well in contrast to ones that didn't, so the author can look at their own work to see what they did and pull that into the less successful scenes. Characters: For this section, I talked about all the characters except the main character and their arc, which is the next section. Here is where you should things like the number of named characters (overall or in a particular scene were there too many? Too few?), the names of characters (were any too similar? Did the author accidentally use a celebrity/infamous/famous character name?), and the purpose of side characters (could any be combined? Did you mix any up? Was there someone you felt was missing?). Positive feedback can go here too, like naming a favorite side character and why, mentioning a great character moment, etc. Character arc and pacing: I followed Save The Cat Writes a Novel as my guide for when certain beats should have hit, and used that to inform me on pacing, though often I could tell by gut if anything was running too long or happening too soon. Save The Cat acted like a nice quantitative measurement to back me up and help the author figure out how much to move their beats. The same is true for pacing plot and pacing the character arc. They should be two separate sections in the edit letter, despite the similar method. Character arc is the beating heart of a novel, so be sure to pay special attention to it: did the character complete their arc successfully? Did they have a lowest moment? Was the character arc driving the plot arc or vice versa? (The "correct" answer for that one will depend on genre, though agents right now love to talk about character driven stories.) Dialogue: Feedback here should include whether the dialogue felt natural in general (there will always be exceptions, like a character who is using a second language might be a little more stiff), if dialogue from different characters felt too similar, and if the dialogue to narration balance felt correct. That last one will depend on genre and taste, but go with your gut. This is also a place for positive feedback: did anyone have a great one liner that made you laugh? Did any character have stand out dialogue in general? Plot Holes: A little more general than the plot beats discussed in the pacing section, the plot hole section is where you discuss other problems with the plot or world. Even if set in the real world, there can be holes (for example: you may have to tell your author that Interstate 80 doesn't go through Colorado, it goes through Wyoming). More often, you'll need to point out questions that come up around "why did the characters do X and never even thought of the much easier method Y?" You may, but you don't have to, suggest possible solutions. However, don't get attached to your ideas, as the author may come up with a different solution that works better for them. If there are other thoughts or comments you have left over, feel free to add more sections. For different genres, you may need other sections such as Romance, Magic System, Alien Culture, Mystery Elements, etc. Every story will be different, so feel free to write an edit letter that best suits the manuscript you're editing. In the end, you'll send your edit letter to your author and hope for the best. Keep in mind, everything you're written in your letter is a suggestion, not a legal requirement. If the author loves and incorporates all of your feedback, hooray! If the author ignores every word you wrote, well, it's their novel. Odds are, something in the middle will happen, and that's great too. All you can hope for us that the author takes away at least one thing from your letter to make their book better in their eyes. Some Quick Don'ts

Have you ever done or received a developmental edit? Was it worth it? Do you recommend your editor? Let's discuss in the comments! If you're friends with any writers, there may come a time when you're asked to beta read their book. Maybe you're a writer yourself, maybe not, but either way beta reading is different from reading a typical book. If you've never beta read before and don't know how, this post is for you! Here are five steps for how to beta read.

Step 1: Upfront Questions Before you agree to beta read, ask the writer some key questions. Your goal is to determine if you're the right audience for this book. Ask for: genre, age group, word count, brief pitch.

Step 2: Set Expectations After you agree to beta read, ask the writer what their expectations are.

Step 3: The Read Now you're ready to read.

Step 4: Summary After your finish reading, you may have some overall thoughts to put together in a summary.

Step 5: Letting Go

Ready to go beta read? Have more advice for beta readers out there? Let's discuss in the comments! I couldn't get the pencil to sit behind Wilbur's ear, but otherwise, it's a pretty close re-creation! Photo by Kate Ota 2023. Story Genius: How to us Brain Science to Go Beyond Outlining and Write a Riveting Novel by Lisa Cron is one of those writing books that I constantly hear about. After my lackluster experience with the similarly lauded Bird by Bird, I worried this would also be a stinker. However, I had an hour to kill at a Barnes and Noble, and when I spotted Story Genius, my curiosity outweighed my hesitance.

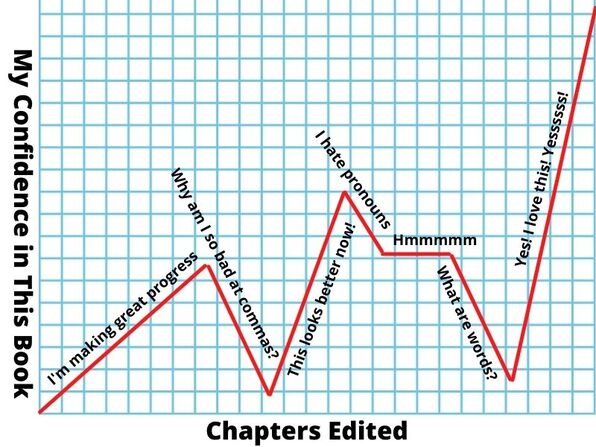

Overview Story Genius breaks its advice into a couple sections, but in general it gives instructions on how to plot from idea through first draft. The main focus is to create a story that has a cohesive character arc and an external plot that specifically drives that arc. It also includes how this approach appeals to the brain so well. There are templates and spots where the book instructs the reader to stop and do an exercise that builds toward having a draft. My Experience I highlighted so much of this book. From the advice on point of view to the tips and tricks for each stage of brainstorming and outlining. This book really appealed to how I usually plot anyway, but added ideas to make that even better. I can't wait to try this method, not just with a fresh story but use it on my current WIP to make sure my external and internal plots mesh well. Is It Worth It? I bought a paperback for $14.99, but if e-book is your thing it can be yours for $9.99. Honestly, this book is precisely for the type of writer that I am. I wish I'd bought it sooner, because I think I'll incorporate its method into every project from now on. I think this book is 100% worth the price! Have you read Story Genius? Have you used the method? What did you think? Let's discuss in the comments. My editing experience in a nutshell. Image by Kate via Canva 2022 Since the end of December, I’ve been working on my novel’s edits with the goal of querying in February. The past two weeksI sent each chapter (all 104 of them!) through ProWritingAid. (This isn’t sponsored, but imagine how much more enthusiasm I’d show if it was?) It was a grueling process, mostly because ProWritingAid takes time to load between each button, and each button reveals information to read and analyze. The logo of ProWritingAid. I've had it for several years now and have no regrets about paying the lifetime fee. The buttons I used most were style, grammar, overused, sentence length, pronouns, and consistency. Based on the feedback ProWritingAid sent me, I accepted 675 suggestions from the software in the last two weeks. Lordy. Grammar improvements took the forefront with 493 suggestions, and 182 suggestions were style improvements, like removing passive voice and overused words. This is the tool bar of ProWritingAid. Pronouns, consistency, and other choices are under more reports. My most overused words (that I culled) were: had/have, could, know/knew, think/thought, and was/were. According to the software, I only overused “just” in two chapters! That’s a huge improvement from my last WIP. I also reworked many sentences to cut down on how many pronouns began sentences. Luckily, I didn’t have many consistency issues or repeated sentence starts. My biggest issue in grammar was comma placement. I’m not surprised.

Don’t get me wrong, I didn’t blindly accept every suggestion. In fact, I rejected most of them. Incorrect assessments of commas, incorrect assumptions about word choice and spelling, and incorrect identification of passive voice were common suggestions I ignored. This is the other part of why this took so long! If I blindly accepted across the board, my story would be a mess. The last leg of my editing journey is a final read-through. I’m not letting myself edit anything unless I’m removing words or fixing typos. I’ve gotten it down significantly from where I started, but I’d still love to lose another 4k. We’ll see if that happens. Have you used editing software in the past? What have you noticed are your editing patterns? Let’s chat in the comments! Clue did not think this book was thick enough to make a good pillow during his nap. Photo by Kate Ota 2021 Marcy Kennedy’s A Busy Writer’s Guide series has been on my radar for a while, though I wasn’t sure which one to read first. After getting some helpful feedback on my rejected Pitch Wars manuscript, I decided to read Deep Point of View.

Overview All the Busy Writer’s Guides are short, and Deep Point of View (POV) is no exception, with the paperback clocking in at 150 pages. The book explains what deep POV is in a large sense, then chapters break down various specifics within the deep POV umbrella. The last section includes a step-by-step guide to check if your own writing is deep enough, including lists of words to search your document for that may indicate a shallower POV. The book also gives you access to a printable copy of the guide you can use again and again. My Experience The book was a quick read. The downside is that I had already known most of it. There were a few sections where I highlighted some new info, but after going back through I see I only highlighted on five of the 100 pages prior to the step-by-step guide. Not great odds. Honestly, my writing groups talk about most of this stuff already. And yet, I’ve been told my POVs aren’t deep enough, so clearly, I needed the reminders. Is It Worth It? I think it is. My paperback was $9.99 plus shipping, which seemed to be a consistent price across online indies and Amazon. There’s also an e-book option ($4.99) for those who don’t plan to highlight it or don’t want to wait for supply chain problems to resolve. I haven’t seen it in a physical bookstore anywhere (yet). I think it contains good info, especially if you’re a writer who is new to deep POV, struggles with deep POV, or doesn’t have a writing group who can check your POV. The checklist at the end is a great resource as well, which stands out among other books who tell you what to do in theory and then just have you go try it solo. It was an easy, quick read for—wait for it—busy writers. And there wasn’t a whole lot of fluff or padding, even in the examples. I appreciated that. I’ll probably check out other books in this Busy Writers series as well. Have you read any of the Busy Writer’s Guides? Did you find them worth the price? Let’s discuss in the comments! Wilbur loved The Anatomy of Story so much, he kept rubbing his face against the cover. Photo by Kate Ota 2021 I picked up a copy of The Anatomy of Story by John Truby months ago and let it languish on my shelf. I thought I’d read once I was done editing my current project or maybe when I started querying. However, as I started prepping for NaNoWriMo (during which beta readers will have my current project) I realized I should take a look to see if this book would influence my Preptober.

Overview This approximately 400-page book is $18.99 for the paperback. It’s like going from Save The Cat and The Story Equation and taking the next step in writing mastery. It includes character creation, setting, theme, and twenty-two story beats. There are numerous examples throughout as well as worksheets. My Experience The story beats are a bit save-the-cat-ish, but those were hardly the best part of the book. I appreciated the analysis of character creation and scene setting that’s explained before plot gets brought up. The way different elements are discussed on a symbolic and thematic level was mind blowing. I even found I’d used some of the techniques on accident (probably from reading so much—hence why you need to read a lot!) and with some tweaking I could make it look very purposeful and deep. I hadn’t seen many of the major examples (Tootsie, Casablanca, and The Godfather were most referred to, and I hadn’t seen The Verdict either) but they were clearly explained. I had seen some others (It’s a Wonderful Life) so it was helpful that most concepts were explained using multiple examples. It’s a dense book. I tried to read it on my morning commute and fell asleep a couple times. You really need to be awake and committed to reading it. However, it’s dense with knowledge and supremely helpful. Is It Worth It? The price was great for the amount of information and length of the book, in my opinion. If you’re a person who likes to highlight and flag craft books, then the paperback is for you. If you aren’t a highlighting type of person, then go with the e-book version to save some money. I recommend this book if you’re looking to up your plotting skills. If you aren’t a plotter, I recommend a little more clear-cut plotting book first (like Save The Cat). It’s also not about basic sentence mechanics (for that I recommend It Was The Best of Sentences, It Was The Worst of Sentences) and while it covers character, I think you need a baseline of character building first (such as understanding want vs need; I recommend The Story Equation). I painted this wall during a mini-reno on my house. Why it's included will make sense by the end of the post. Photo by Kate Ota 2020 First drafts are often joked about and called things like dumpster fires or garbage drafts. They’re a way of getting ideas out of the writer’s head and onto the page. After all, you can’t edit something that doesn’t exist. First drafts will vary widely based on your writing methods. Plotters will have fewer problems than pantsers (usually), and some people would rather get it right on the first try than just get it down. However, with NaNoWriMo on the horizon, and many people about to write as many words as fast as they can, I thought I’d write about how I take problems spotted in the first draft and utilize them later.

Info Dumps A classic first draft problem, info dumps tell your reader all about the world or the character in one giant section. Not only is telling (vs showing) a potential issue, but info dumps ruin any tension that’s been built and slow the pace. Readers may end up skimming instead of absorbing the information. When you recognize an info dump as you edit, copy/paste it into another document where you keep your notes about the book (worldbuilding, names, etc.). I use Scrivener, so I have a whole folder where I keep this type of stuff. You can then bring back little chunks of info as they become relevant. I like to highlight sentences whose information I’ve added back, so I don’t accidentally repeat myself. Info dumps help you keep track of your world and get you into the mindset, so if you end up taking a break, you can read the info dump to get back into the manuscript. Dropping Characters Have you ever started a book with a cast of characters, but by the end you realize you haven’t mentioned one guy since chapter 4? Oops. It happens all the time. This means that character wasn’t as important as you initially thought. Maybe they aren’t needed at all, and you can take this mistake as a sign you should delete them all together. However, if they matter up front but clearly not later, you can also get rid of them in a way that adds to the story, such as acting as a red herring or increasing tension. Plot Holes Much like pot holes, plot holes make for a bumpy ride in a book. You should try to fill as many as you spot in your edits. However, rather than just filling a hole with the first thing that comes to mind, or the easiest thing to write, take the opportunity to dig a little deeper and see how you can enrich your world, characters, or plot while also filling the hole. It’s like those home renovation shows where they discover bad pipes and they say, “we could just replace the pipes in this bathroom, but eventually the whole house will need to have it redone, and if we do that, it means tearing out all that ugly paneling to get to the pipes behind it.” The wise choice is to rip out the paneling and replace all the pipes, if they have the budget. Since enriching your writing doesn’t cost money, go ahead and rip out the paneling. And the shag carpet, while you’re at it. Off Balance Scenes Some scenes will have too much narration, others will have too much dialogue. This is something you’ll want to balance out, but worry not. This mistake has actually highlighted for you what matters in that scene. Is it all about the dialogue? Then the narration you add in the next draft should be focused on the characters reacting to the dialogue and be less about stage direction. Is it all about narration? Then the dialogue you add shouldn’t be distracting from that and should instead voice the most important internal realizations. Underwriting Perhaps your first draft clocked in at about 60% of the expected word count for your age group and genre. This tells you that something is missing; characters, sub plots, setting or other descriptions, internal narration, etc. It will vary for each writer, but once you notice a pattern in where you skimp, you’ll know what needs to be added. For example, my early drafts lack emotions and reactions, so now I automatically put that in my editing to-do list. It may take more than one book to recognize where you could use more words, but once you know your first draft skinny points, you won’t even need to look to know they’re there. These can then become strengths of your next draft, since you’ll be putting conscious effort into adding these items. Overwriting The opposite of the last problem, if you overshoot your genre and age group’s expected word count, you’ll need to do a little cutting. Ideally, you won’t just delete, but keep removed scenes/paragraphs/sentences in another file for later. You can always come back to these and bring back little pieces to supplement the next draft. It’s easier to squirrel a scene away than it is to delete it, and you may find this strategy makes it emotionally easier to cut words. Identifying what to cut is harder, but if you compare your story’s beats to an established beat sheet (ex Save the Cat) you may be able to identify plot elements that take longer than expected and start hunting for what to cut there. The main benefit of overwriting is that it’s faster to cut than add words. Let's return to my home reno example from earlier. Basically, in a first draft you’re establishing what’s important. That’s setting the blueprint and foundation of the house. Building up the studs and deciding where walls go. First drafts are asking how big is the kitchen, how many beds and baths, is there a basement or a second floor. You don’t need to worry about which poster is going to hand above your desk in your home office. Sure, you can buy one if you see it and have it ready to hang, but the focus is going to be on bigger stuff first, by necessity. Yes, a home reno is messy with painter’s tape and loose nails and dust on everything. However, that’s because it’s not the final step yet. So don’t think of your first draft as garbage, think of it as the start of building a house. How do your first drafts go? Are you a plotter or a panster? Do you over or under write? Let's discuss in the comments! Point of view? What about this stunning view! Banff, Canada. Photo by Kate Ota 2018 Remember last week how I ended by saying that my next post would be about trimming words? Well, despite deleting a chapter, I’ve managed to add 1000 words to my WIP. So, I’m going to go ahead and say I’m not qualified to write a word trimming post just yet.

It’s been a while since I added to my Easier Editing series, so I decided to write about one of the things my first round of beta readers said I did really well. Let’s talk about how to make different POVs in the same book feel like different people. They’ll all have your author voice naturally, so what you need to do is make them feel distinct from one another. The goal is that a reader should be able to put your book down, then come back and know who the POV character is without flipping back to the last chapter or scene break. (Need a refresher on POVs in general? I have a post for that!) Here are the top things I do to accomplish unique POVs in a multi-POV book. Word Choice Once I build my characters and understand who they are, I decide what kinds of words they’ll use. A laboratory researcher might use precise and scientific language. Creative characters would use more colorful language. Someone really into trains might make analogies that always go back to trains. Also keep in mind what words your characters might not know. Think of Disney’s Ariel, who called forks dingle-hoppers because she’d understandably never heard the word fork. Perhaps you have an older character who wouldn't know teen slang, or a teenager who would be less likely to know name brands of alcohol. Motivation Whatever is driving your character is bound to be on their mind. Think of a conversation between two characters. If told from one POV, the interaction may be boring pleasantries ending with a refusal to hang out. How rude! When told from the other POV, we might learn how this character is desperately avoiding anyone coming over and discovering the dead body in her basement. Something that urgent is going to color the narration significantly. Less urgent goals should still have an impact, too. Attitude I tend to choose if my characters are overall optimistic or pessimistic, and then what mood they’re in for each scene. I end up with things like angry optimist, happy pessimist, irritated pessimist, etc. It’s much easier to write a specific voice knowing that combination of world view and mood. Frequency It’s easier to have a very wild, quirky character voice if they don’t come up often. It’s harder to sustain and use that voice to convey complex plot points. You don’t want to get so niche that this character describes something and your reader is left with no understanding of what just happened. Let’s use an extreme example. Think about Shakespeare being read in modern classrooms. You read that aloud as a class and then the teacher had to explain what that entire scene meant. Yes, it’s in English, but man oh man is that Elizabethan voice difficult to decipher for modern audiences. If one of your POVs was written so uniquely, they’d stand out, but not in the way you want. However, if you toss in a relevant sonnet every now and then, you won’t lose your reader because they’ll trust you to lead them back to the more digestible story soon. That’s my basic strategy for differentiating POVs in my multi-POV WIP. Do you have different strategies you use? Let’s discuss in the comments! |

Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed