|

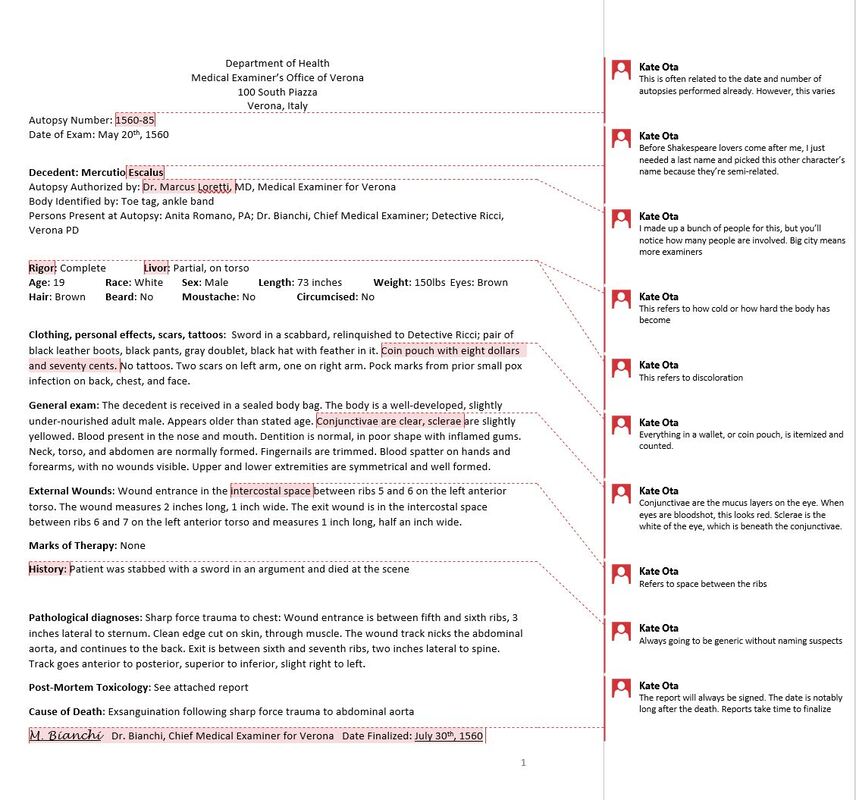

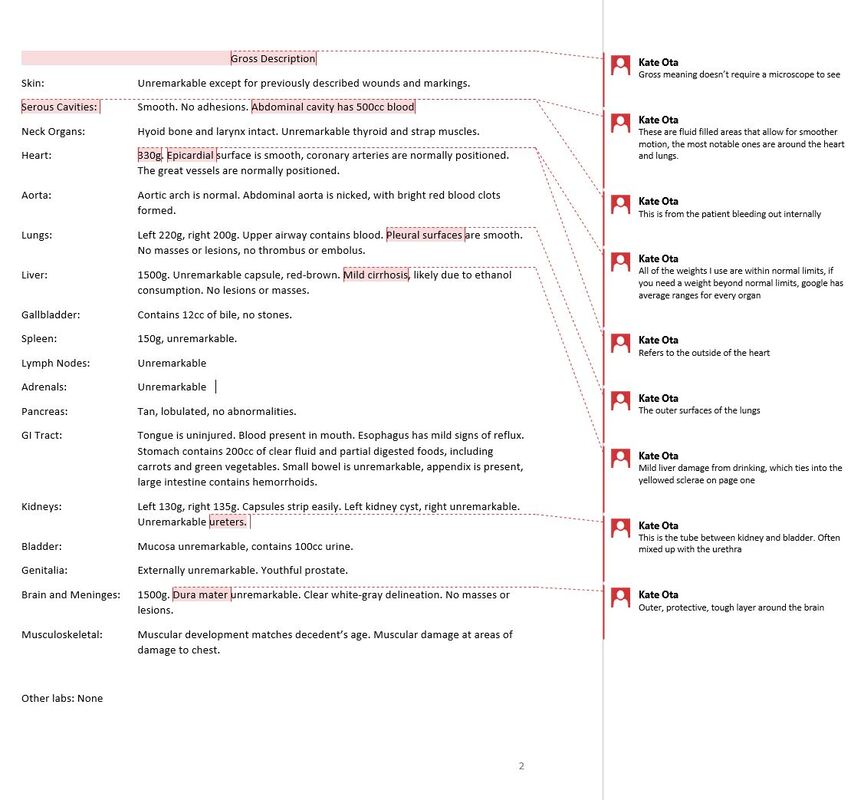

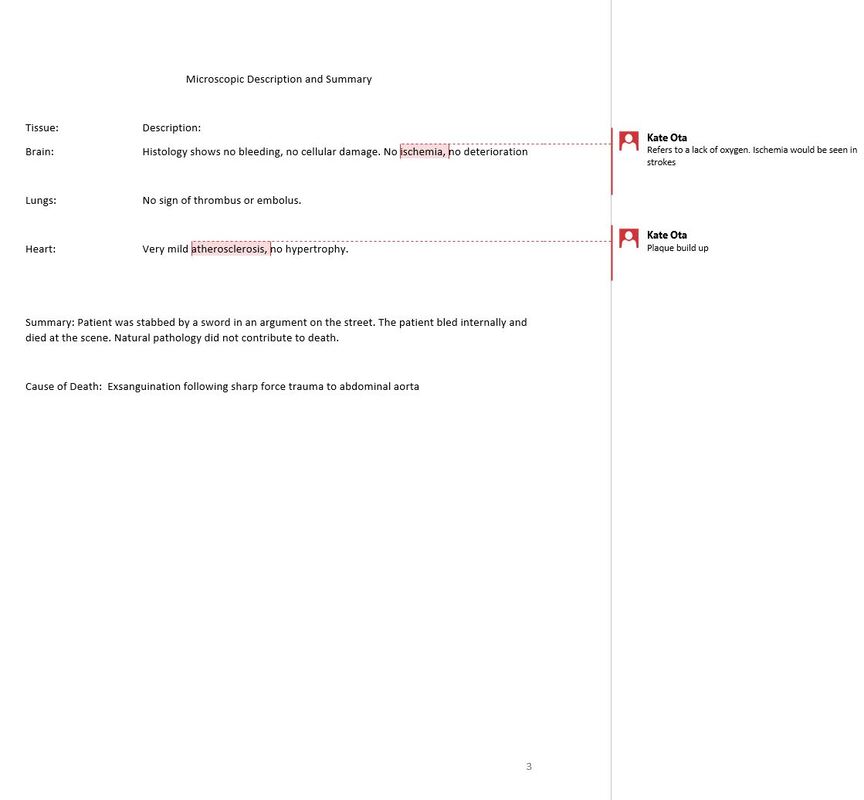

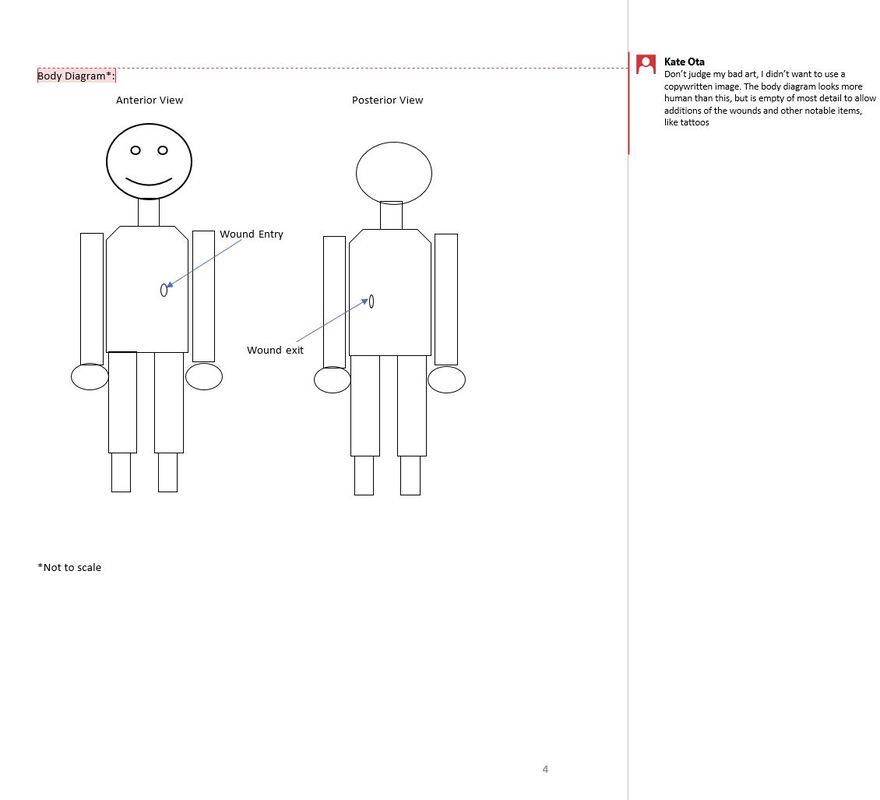

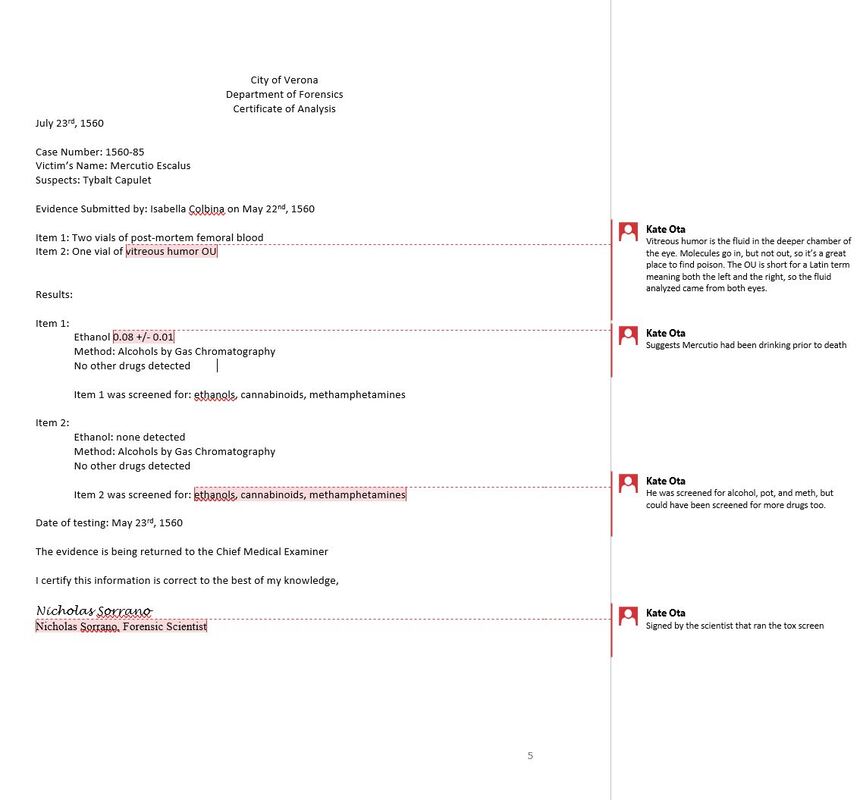

To expand on my last post, I wrote a fictional autopsy for a famously murdered character in the public domain, Mercutio of Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet. I took a lot of creative liberties here because we don't get a ton of Mercutio description. I learned that writing a character's autopsy is a great way to get to know them, maybe try it as a character building exercise! The annotations on the side are meant to be helpful and clarify anything I felt wasn't common knowledge. The following autopsy is completely fictional and any commonalities with real people is pure coincidence. There you have it, folks! Was this example helpful? Want more examples? Want to make fun of my goofy body diagram? Let's discuss in the comments!

1 Comment

Photo is of my parents' Japanese Maple tree. It's red and kind of like blood vessels if you squint. Photo by Kate Ota 2019 From murder mysteries to space operas, an autopsy can appear in all sorts of genres. Either a scene or a paper copy of the report can help clarify the cause of death for the characters invested in the outcome. Most people have never read or performed an autopsy and because of their legal and highly personal information, it’s hard to find reliable examples online. I’ve read dozens of autopsy reports as part of my day job. Here’s what you need to know about what an autopsy report contains.

Types of Examiners Between different districts, the formatting of the autopsy report will vary, so don’t get stuck there. It’s the content that matters. Who performs an autopsy will also be different, there are Medical Examiners (ME) and there are coroners. You’ll need to research where your story is set (if it’s the real world) to learn who runs things. These offices may also have other employees who help the Chief ME or Lead Coroner, these employees may have titles such as Investigator. Autopsies may also be performed by pathologists at the hospital, but this is generally outside of the legal realm. This occurs when either the hospital wants to see what they did wrong, prove they didn’t do something wrong when someone dies in surgery, or if the family pays for an autopsy after the ME/coroner declines. (Side note: private autopsies requested by the family can be crazy expensive!) Types of Exams In my experience, an ME/coroner also has two different types of post-mortem examinations. A view is done usually when cause of death is fairly clear, like a hanging or car accident trauma. An autopsy is more in-depth in detail and includes internal and external exam information. Usually this is for cases that may become court cases, like a potential homicide. Content An autopsy report will always include: who performed/was present for the exam, the decedent’s name, age/DOB, physical description, overview, cause of death. This is all written in the clearest phrasing possible, and with scientific terms only (example: clavicle instead of collar bone.) The physical description includes hair and eye color, beard, mustache, circumcised (these last three are yes, no, or N/A), scars (surgical and non-surgical), tattoos, condition of skin/teeth/nails, weight, and if the person appears their age. The overview will include things like signs of trauma, signs of medical intervention, and any medical information the autopsy uncovered, even if it’s not the cause of death. These incidental findings can include mild heart disease, nodules or cysts on organs, lung disease like asthma, etc. Cause of death is very specific and technical, since this is a legal document. Be sure to research medical terminology to ensure the report states what your plot requires. If your autopsy report needs to say, essentially, “we don’t know why this person randomly died,” call it acute coronary insufficiency. This means the heart gave up all of a sudden. An autopsy (rather than a view) will also include detailed descriptions of each major organ (including their weights) and descriptions of any microscopic slides made for the investigation. Slides are only taken from areas relevant to the suspected cause of death. Often this is done to determine if a medical condition contributed to death, such as cardiomyopathy or a pulmonary embolism. Finally, in either homicides, suicides, or anything involving a motor vehicle, the odds are high the investigator will perform a toxicology screen. Generally, this will screen for alcohol, major illegal drugs, cannabinoids (legal or illegal), and forms of these drugs left after the body breaks them down. Other drugs or substances may be screened for if signs of their presence were at the scene of death, like an empty bottle of antidepressants or rat poison. Tox reports screen blood, urine, vitreous fluid (from the eye), and sometimes other fluids, like bile. They’re also stored for later screening if necessary. Common Medical Terms

Examples of Cause of Death Phrasing

I hope you found this autopsy overview helpful for your writing. Have any questions? Need help rephrasing your project’s cause of death to sound more scientific? Let’s discuss in the comments! Photo of a boat without the sail up, which makes it look unfinished. Like the book I put down forever. Photo by Kate Ota 2019 Rather than write a negative review of a very popular book that I couldn’t finish, I decided to write about what I learned instead. Why couldn’t I finish it? Can I avoid my book having the same fate? Can I help your book avoid the same fate? Let’s hope so.

An intriguing opening scene doesn’t mean the next few chapters can be an info dump. Yes, start with something exciting and interesting. This book had a very strong first chapter with a scene that was completely unique and will probably stay with me for years. Unfortunately, the next fifty pages were backstory. All I wanted was to get back to that opening (which had a dead body) and work on solving the mystery. I didn’t care about the main character’s sad childhood, especially not on pages 10-60. If it was pages 210-260, after I knew and liked the main character, then I could empathize. The main character needs agency. This main character of this book did a lot of looking. Watching. Observing. Seeing. Not a lot of action. While the dead body was initially exciting at the opening, when the main character did nothing but stare and watch others, I got annoyed. In fact, I questioned if this should be the main character at all, since she was the least interesting person in several scenes. Flashbacks kill pace. It was like being in stop-and-go traffic. The plot would creep ahead, then freeze for backstory. Don’t get me wrong, flashbacks have a place in storytelling, but they need to be strategically placed. This story had multiple flashbacks per scene, often without warning, and the timeline became murky. The flashbacks also didn’t help move the story forward, and often repeated information. The other problem was that theses flashbacks were told, not shown. Meaning the character was thinking about what happened, not showing the reader in a scene. Great for unreliable narrators, but this was overkill. Wondering how long I stuck it out? I got to about page 100 of a 400-page fantasy. By that point in a story, I need to be hooked and invested. This story had barely gone beyond the inciting incident. At least I learned why, and won’t repeat these issues. Did you ever set a book aside without finishing? I recommend going back and learning why, you never know what you may learn! A beautiful tree in Davis, CA. Many people study disease at UCD. Photo by Kate Ota 2015 Books and movies love disease. Whether it’s the crux of the story, like a zombie-fying outbreak, or it’s background to other elements, like in Marie Lu’s Legend. Sometimes we need to include a real disease in a historical novel, or a fake one in fantasy or sci-fi. For a real disease the method of how to write it is clear—do the research and maybe read some other books (novel or non-fiction) that include it. But to make one up is a whole other ball game. I took many courses in undergrad and grad school that discussed disease from all angles. No need for you to take an epidemiology course though, I’ve gathered my knowledge and have the top five tips for how to make up a disease right here!

Determine a Method of Transmission For most zombie stories, the method is a bite. But there are many ways to catch a disease. Here are the main methods: Person-to-person is when body fluids (wink wink) are exchanged to transmit fluid. Transmits slowly through a population, but tends to be pretty infectious. Examples: HIV, Hepatitis B, syphilis, and other STDs. Droplet transmission is exactly what you think it is. Jessica has a cold, sneezes in your face, you breathe in her mucus droplets, and now you have a cold. These tend to transmit quickly through a population, and can range from mild to deadly. Examples: common cold, flu, tuberculosis. Airborne or contaminated object transmission is similar to droplet transmission, except you don’t need to be close. These diseases can linger in the air or on a surface long after someone has left the room. These are also often quite contagious. Example: measles. Food/water borne diseases are exactly what they sound like. Often, they cause digestive symptoms and place like the FDA monitor for them. These are often killed in proper cooking or boiling processes, so they tend to have a class divide. Examples: E. coli, cholera, botulism Animal-to-person contact and zoonotic diseases tend to be rarer now that most people only interact with household pets instead of farm animals or game. Many diseases stay in animal populations and rarely make the jump to humans, like rabies. A more common disease to crossover is Toxoplasma gondii, which is transmitted by cat poop. Humans tend to be very bad at fighting these diseases because the germ evolved with a different host. Therefore, they can be very deadly to humans while natural host animals survive better. Another example: black plague (rats/prairie dogs). Some diseases begin as animal-to-person, then can be transmitted person-to-person, like Ebola. Insect bites (aka vector-borne diseases) transmit many problematic diseases. Mosquitoes, fleas, and ticks are the main offenders to humans. Often, the insects pick up the disease from another animal host. Ticks get Lyme disease from infected deer and mice, then introduce the Lyme to humans when they bite us later. Insects like warmer climates, so vector-borne diseases are more of a health hazard in the tropics than in arctic zones. Other examples: malaria, West Nile virus, Zika The environment also hosts many disease-causing agents. Parasites like ringworm, hookworm, Legionaries, flesh eating bacteria, the list goes on and on. Humans catch this by being exposed to dirty water, soil, etc. especially with open wounds. As you may have guessed, rates of these diseases also tend to have a class divide. Morbidity and Mortality Rates Once you have your method of transmission, you should determine the morbidity and mortality rates. Morbidity is the state of being sick. The morbidity rate is how often people are catching it, you can think of this as representing how contagious it is. Mortality is the state of being dead, so the mortality rate is how often it kills the person it infects. You can think of this as representing how deadly this is. Plague-level events have both high morbidity and high mortality. Something like rabies has low morbidity, because it rarely happens in humans, but once contacted it has high mortality. The common cold has high morbidity in the winter, but very low mortality, as few people will die from it. In your writing, you should determine how present you want this disease to be. If your fictional disease has high morbidity and mortality rates, it better be the main plot focus. Otherwise, it may be too distracting for your reader. Consider how it is transmitted in determining your rates, see the section above. Symptoms Symptoms of a disease are your body trying to fight it off. Fevers are from your body trying to boil that disease to death. Snot is from trying to get that disease out of your nose. Coughing is to get rid of the mucus that trickled into your lungs. On and on. You should think about what symptoms your fictional disease has and why. Tie the symptoms together, like high blood pressure causing headaches, a rash leading to sores, runny nose leading to sore throat. And have the symptoms escalate through the course of the disease. This is not only realistic, it adds drama to the story, and helps your characters keep track of how close a comrade may be to death. (We only have until she develops a fever to find a cure! After that, she’s a goner!) Scars Not all diseases leave no trace. Smallpox left people with large scars on their skin. Ebola can change a survivor’s eye color (and continues to live in the eye!) Scarlet fever can weaken the heart. Chicken pox can come back as shingles. Malaria never really leaves you. If anyone is able to survive your fictional disease, consider the after-effects that may remain. It may be a somber reminder of what they endured, but it could also have social consequences, like facial smallpox scars. Cure If the plot or a subplot revolves around developing a cure, then you’ll need to figure out a cure. Even if you have a scientist pop up and do a little hand waving, you’ll want to know more than just, “you need this injection! Ta-da!” There are several places in the cycle of disease transmission in which you can stop the disease. Let’s discuss those: The agent: Identify the disease agent; a virus, bacteria, parasite, fungus, and discover what will kill it outside the body. Bleach? A bacteriophage? Gotta identify the problem before any other solutions are found. Identifying the agent is usually early in the story. The exception is a fantasy with a historical world, pre-Victorian era or earlier, in which germ theory was not developed yet. In that case, this step and many others, may not apply. The reservoir: This ties back to how it’s transmitted. Once that’s known, the reservoir can be handled. If it’s on dirty surfaces or in the water supply, those can be cleaned. Animals can be treated, insects can be sprayed for. If it’s person-to-person only, we’ll get back to that. Take note that hospitals will often adhere to the assumption that everything is contaminated and can transmit the disease and will be cleaning through the process of treating patients. But if you’re writing a fantasy with a historical flavor to it, maybe hospitals don’t apply to you. Portals of exit and entry: How does the disease get out of one person (portal of exit) and into another (portal of entry?) Once that is found, your characters will know if things like face masks, gloves, hand washing, and different levels of personal protective equipment are helpful. For anything particularly infectious and deadly, hazmat suits might be used before this information is available and once this is known, the medical teams will step down their equipment. Susceptible hosts: The disease can only keep going as long as someone is susceptible to it. Part of disease treatment is prevention, often an immunization is developed to protect those who haven’t been infected. But it could also be as easy as hand washing and basic hygiene, like in common cold prevention. A cure: Maybe you want a real cure that can help those who already have the disease. This will be dependent on all the other factors you have developed. Maybe you’ll choose a vaccine for your virus, an antibiotic for your bacteria, a substance toxic to the parasite, or maybe your characters will treat the symptoms until it passes. It all depends on the rest of the world building you’ve done to this point. If the disease’s mortality rate is high, the cure will be preventing it—sorry to anyone who caught it. If the mortality rate is especially low, there may be no pressing need for a cure. Just remember that the cure needs to kill the disease agent without killing the host. Need more inspiration? Choose a morbidity rate and mortality rate to mimic and search for similar diseases. See how different organizations handled it, from Venice inventing the quarantine for ships with possible plague to how the WHO contains Ebola outbreaks. Found any of these tips helpful? Have any fresh ideas to add? Let’s discuss in the comments! Had an adrenaline rush when two rhinos ran across our path about three yards ahead. These were not those rhinos, we had no time for photos then. These rhinos were nice and calm. Photo from South Africa in 2011, taken by Kate Ota. I earned a Masters in Molecular, Cellular and Integrative Physiology, and the part that I’ve used the most is the integrative aspect. Classes taught me not just what one signaling chemical does, but how it impacts others. Some of my favorite things I learned were why alcohol makes you urinate way more than any other beverage, why nicotine is so addictive, and how epinephrine (aka adrenaline) impacts your entire body.

I thought it would useful to discuss how adrenaline impacts the body, because any good story is going to have a scene where your character feels that shot of adrenaline—whether it’s from fear, excitement, or a combination of both. The section called “how your character will feel” discusses how to show the impact of adrenaline for each part of the body. Adrenaline is produced in the adrenal gland, which sits on top of each kidney like a party hat. It’s a hormone, so it travels through the blood. Therefore, it has access to and impacts most of the body. It prepares you for sudden physical exertion as a reaction to a stressor, like a bear or an important exam. Let’s break this down by body part: Blood vessels/muscles What happens: Some vessels will dilate (widen) and allow more blood to flow through them. Some will constrict. It all depends on location, location, location. Skeletal muscles, the ones you have conscious control over like those in the legs and arms, have lots of blood vessels in them. These blood vessels will dilate to deliver more oxygen to the skeletal muscle. Afterall, you need those muscles to run or fight. However, adrenaline decreases the activity of smooth muscle, which you don’t have conscious control over, like what lines your intestines, for example. You don’t need active intestines to fight or run. Vessels delivering blood to the digestive system, urinary system, and reproductive system will constrict, allowing blood to be sent where it’s most useful for survival. But why do people sh*t their pants or urinate when they’re scared? So glad you asked. It’s because the smooth muscles at the end of your large intestines and in the bladder also relax, and if there was something in the rectum waiting to be released at an appropriate time or a lot of pressure within the bladder that was being held, well. You didn’t need that extra weight slowing you down anyway. How your character will feel: They will have warm, reactive muscles, which will be able to produce more power than usual. If they were hungry/turned on/in need of a bathroom before, this will no longer be a major concern. There’s a reason why most fight scenes don’t include the inner monologue wondering about lunch or the bathroom—those systems are suppressed. Heart What happens: It beats faster and harder. This will increase blood pressure. Pretty straight forward. How your character will feel: pounding heart, maybe feeling the heartbeat in their head, even a headache if the stress is chronic. Skin What happens: Welcome to Sweatytown, USA. Now that those blood vessels around muscles are dilated, there’s more blood going through muscular areas. That blood will lose heat through the skin when it passes near the surface, so the skin is generally warm over big muscles. The muscles themselves are also producing more heat as they’re used. But remember, the body can shunt blood away from things less necessary to fighting/flighting, so some people also experience very cold hands. (Who needs fingers to run? Apparently not you.) Also common: pale (as in bloodless) faces, which flush again later after physical activity or embarrassment. How your character will feel: Sweaty palms and armpits are most common for emotional stressors like running into a crush or a big test. For physical stress, like seeing a bear and realizing you need to run (not the recommended method of bear safety), they may get more of an all-over body sweat. Lungs What happens: Faster breathing. Get that oxygen to those muscles! Some people will take short shallow breaths, but that’s not going to get enough oxygen in there, and these individuals may pass out instead. Adrenaline also relaxes the smooth muscle in the lungs, which opens the airways wider in the hopes of increasing oxygen. How your character will feel: While most characters will breathe faster, and take deeper breaths, reactions may vary. Anxiety (a chronic stressor) may cause a sense of chest constriction, but the best reaction to that is deep breaths. The character may also breathe faster and shallower, but remember this can cause light headedness, dizziness, and/or fainting. Liver What happens: Adrenaline releases glucose (sugar) from where it’s stored in the liver as glycogen. After all, muscles need the energy in sugar to contract, and the body is anticipating using the muscles a lot. If this ends up being a false alarm situation, like a scare in which there is no actual fighting/flighting needed, the blood sugar may take a while to go back down. This may lead to a lack of hunger for a time afterwards—it varies by person. How your character will feel: There will be a spike in blood sugar. Most characters won’t notice this, but diabetic characters might be strongly affected. Eyes What happens: The pupils dilate to allow more light in. More light = more information. Ever seen a cat about to pounce? Its pupils get huge just before the motion, so they can get more information about their prey. How your character will feel: Tricky, since this is something most people won’t actually feel themselves. But your character may see it in others. It can be shown subtly. For example, if it’s dark, perhaps your character was struggling to see before, but after hearing that wolf howl, they’re able to navigate the dark forest much more easily. Anaphylaxis What happens: Anaphylactic shock is when the body’s reaction to something is so bad, the heart is no longer able to pump, and blood vessels are too constricted. The heart and circulation sections above explain how the adrenaline counteracts that exactly. But remember, it has a short lifespan in the body compared to other hormones, so anyone who experiences anaphylaxis needs medical attention ASAP. How your character will feel: A character in anaphylaxis will have trouble breathing, even chest pain, and may lose consciousness. The EpiPen is injected and they will feel all the effects of adrenaline, but most notably, their heart will pick up the pace. Overall Because the body is now ready to fight or run away at the drop of a hat, the character may experience any of the following: jumpiness, jitteriness, trembling (especially hands), ignoring physical pain in order to focus on an immediate physical task, or palpitations (fluttery/irregular heartbeat). Chronic stressors can cause the release of another hormone, cortisol. And that’s usually associated with more chronic effects, like stress-induced weight loss. Hopefully this list gave you some methods of showing your character’s feeling of excitement, nervousness, fear, or surprise. Did any others come to mind? Does it help to know the physiology behind the feeling? Let’s discuss in the comments! |

Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed